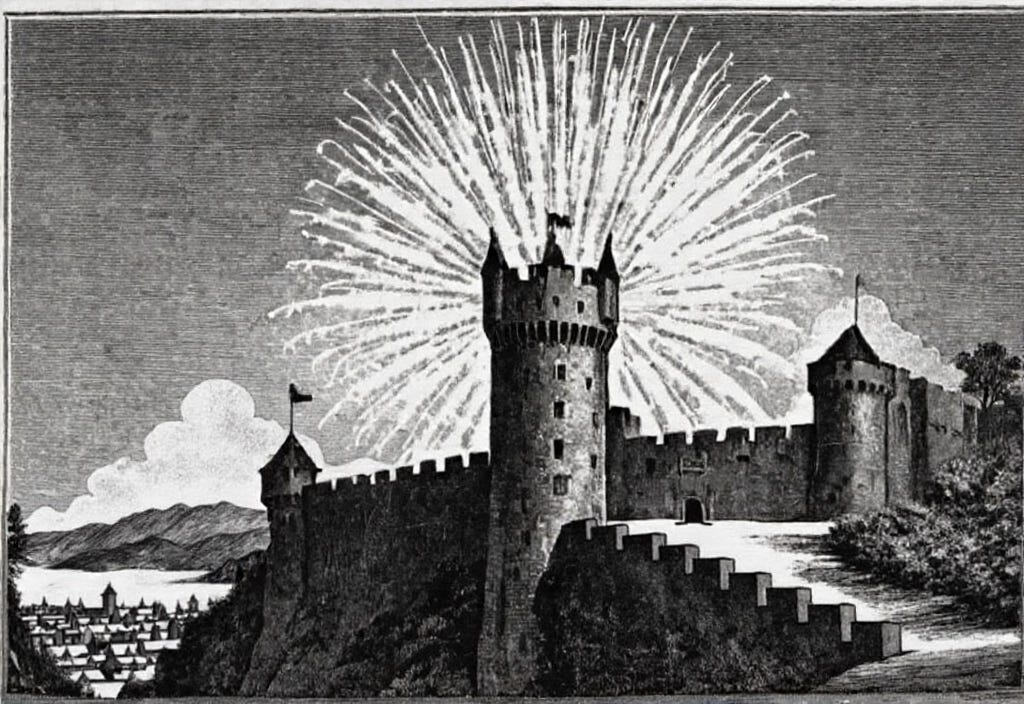

The snow ceased before midnight, and fireworks blossomed above the Castle, fiery streamers in the frosty air. The banquet hall slowly emptied, and the revelers staggered outside to stand in the bailey and courtyards or climb the towers, craning their heads to the pinprick stars and the rockets exploding red and green and gold.

Inside, the celebrations continued along halls and into private chambers. After seeing his wife to bed, Arellwen joined the rest of the council and they toasted one another until Exchequer and Army passed out on the long table where treaties were signed and campaigns plotted, and the others staggered off to find their rest. In the kitchens the feast’s remains were devoured by the scullions, who then discovered an untapped winecask, emptied it quickly, and fell asleep in a heap by the firepit. The grooms and farriers caroused in the stables and tried to entice chambermaids to join them, while the maids encouraged Falconguardsmen to entice them into convenient corridors and alcoves. In the long eastern gallery a gathering of younger lords and ladies diced in candlelight to cheers and shouts and occasional trumpeting belches. In the gardens there was a drunken snowball fight between Heart lords and Ysanis, a gleeful parody of long-gone wars. And in the finer apartments in Burnt Tower, the Janaean ambassadress found her way to Coallen of Ysan’s bedchamber, though what the lady discovered there was reserved for the letters she sent south.

Alsbet wandered through the revelry, her betrothed gone to bed in his tower and her father to sleep in his imperial chambers, but her mind too much of a whirligig to even contemplate following their example.

She was shed of attendants and yet still surrounded, cheered by friends, shouted at by servants grown bold for this night, swept into whirlpools of laughing faces and then flung out into calmer seas. It was a little like that dark evening on the river, but also different, so different — because there she had been elevated, enthroned in an alien place, whereas here she was in her home and among her people, just another young woman out enjoying the festivities, with friends who cheered her when they recognized her, but not a goddess or a sacrifice.

Just Alsbet of Montair, enjoying her own festivities as any betrothed young woman should, with smiles and cheers and drinking all around …

It was not her fantasy of marriage, the fantasy of High House, but perhaps she had clung to that fantasy for too long, letting it blind her to what was good about the Castle, this place where she had become a woman (well, not quite a woman, but so very close …), whose demands she had treated as a trial, but which might have felt homelier and kindlier to her if only she had been able to see through the pall of grief and fear.

All the Castle faces — here the groomsman who cared for her horse, turning a somersault into a snowbank, there the blonde girl among her maids, dancing gleefully with a soldier, there Lord Marfwen the chamberlain, far too old for the tankard he was hoisting — were they really so different from the faces from her youth, the cooks and servants and soldiers from the mountain summers, whom she had loved so well? And how they cheered for her now, as she passed among them — didn’t they love her too, and couldn’t she had loved them better if she hadn’t been so determined to see everything refracted through tragedy, mourning, falling-off?

“Everything falls together, it’s all one mortal thread — the hawk falls as the crow falls as the squirrel falls as rabbit falls as the mole falls as the rest of them fall because it’s all one thread …” The voice of a jester, black-and-white and self-important, who swept her the most obsequious bow — there was clapping from a gaggle of Heart ladies watching his performance — and plucked from the snow, somehow, a single white rose, alive and blooming — and now there was a long ooh from the ladies — and Alsbet took the rose and wondered at the trick and swept him a curtsy in return, and his grin was ivory and he tumbled off, still shouting his rhymes.

Yes, everything falls — her father might not survive without her, just as her mother had not survived the death of Allasyr, and there would come a day when she had to mourn him in her own far-off kingdom, her Bryghala. But when that day came it would do no good for her to think only of the grimness of the last few years. She must think of her father at his best, her father as she had loved him. And when she thought of this Castle, she must think of the people who had helped her through her suffering without her ever quite appreciating it. She must think of the blue sisters, the older ones who had made her feel closer to the angels and the younger ones who had tried to be her friends. She must think of the decency of the chamberlain and not just his prissiness, and remember the Council lords not just as condescenders but as men who had helped educate her in politics. She must think of the moments that had brought her happiness, however shadowed —

— and at just this moment the swirl of the crowd brought her just a few spans away from a bearded man, a laughing lord with a laughing wife beside him, a man whose face without a beard had once ridden boldly toward her box on the tourney field, and given her a crown of flowers and the widest possible of smiles.

It was Lord Raldred Gant, a little older now and married, and she was about to speak to him when a hand took hers, more firmly than most well-wishers even on this drunken night, and she turned and found herself locking eyes with Cresseda.

“May I wish you all the happiness the angels can grant, princess?” the iron duchess said, her voice loud enough to carry but softer than her grip.

“You may,” said Alsbet, letting herself spin away a little from the crowd, Raldred Gant forgotten, the packed slush colder on her feet. “You may, and you may also apologize for insulting my betrothed, your grace.”

Cresseda shrugged, a gracious shrug if that was possible, an undulation in the long white fur she wore. “I would not have sought you out if I did not intend an apology. I am truly sorry. I don’t know what overcame me.”

Then, before the princess had time to speak — “No, in truth that’s false, I do know something of what I was feeling. I can see how you look at this Bryghalan prince, I can see the hope you have for happiness. A woman’s happiness, different from the kind I’ve experienced and different from what I offered you as the wife of my nephew. So I apologize if what I said was laced with resentment or regret.”

“Well,” Alsbet said. “Well. Then I accept.” There seemed nothing else to say.

“I am glad,” the duchess said. “But I wish to say one other thing as well. Hopes are well and good but the play does not always go as we should like, and the good player knows that sometimes she must play a different part than the one she hoped to fill. I want you to remember that, even in your happiness — that the certainty you feel tonight may mislead you, and that you may not be seeing the whole stage. Can you remember that? Whatever comes?”

With Cresseda she always knew there was some deep game, but tonight was not the night for plumbing depths. She tried to say something gracious —

“I can, I will. And I have not seen so much as you, but I have certainly seen enough to know that things are not always arranged to our liking. I can remember that easily, even if I also allow myself a little hope.”

The older woman smiled, nodded. “Indeed. May we all live in such hope. So goodnight, your highness, and a blessing for your forgiveness.”

Then she dipped her head, her white fur made a sweep around her, and she was gone. Leaving Alsbet feeling soured, annoyed, mystified, groping for the mood that she had lost. She turned back to the nearest knot of nobles, but Lord Gant had vanished. A firecracker went off close by, and she started a little at the noise. Someone tried to hand her a goblet, and she tried to wave it away —

“Oh, drink with me, my lady, my great lady, just one drink, for the night’s sake …!”

It was young Morwen, usually her most demure and docile maid, her cheeks a shocking red, her eyes flashing with the sky-colors, her grin as wide as Gant’s had been upon the tourney field. Alsbet let herself grin back, took the cup and drank, shivering as it warmed her, and letting herself say, for once, what she was really thinking:

“She really would have been an impossible mother-in-law, Morwen!”

The maid gave the vigorous nod of the agreeably drunken, and Alsbet let herself be led by her servant toward more groups, more cheers, more happiness.

Behind her on the stamped-down snow, lying where it fallen from her fingers when Cresseda reached for her, the fool’s flower was now a withered thing, its petals browned and cracked, its green stem many long months dead.

“So the trick, it seems, to defeating your empire, is to attack Rendale on Winter's Eve. A pity none of our kinsmen in Capaelya were clever enough to latch on to the idea.”

Aeden shrugged, not really hearing his companion's comment, lounging in the watchman’s spot atop Burnt Tower, beside a pair of drunken legionnaires firing skyrockets that burst orange against the canopy of stars.

He should have been drunk at this point, but he had begun drinking so early that the pleasant dizziness and forgetfulness had worn off by the end of the feast, at which point he had made his way through the crowd to Alsbet, who embraced him and kissed him and told him how happy she was, and he said he was happy too, because what else was there to say? Then she was gone, a flash of gold whisked away from him, with Maibhygon handsome beside her, and nobody looking at him, nobody at all.

“Hmm? Did you hear what I said, Aeden?”

He glanced at the man beside him, an amiable Bryghalan with a narrow nose and a close-cropped beard. His name was Baerys, Sire Baerys mar’ap Something, and Aeden had met him only once before, probably when he first met Prince Maibhygon, seven days ago. He couldn’t recall exactly, but Baerys had remembered him when they collided beside a bonfire about an hour earlier.

“You speak Brethon, don't you?” the young Bryghalan knight had shouted in that language, and when Aeden had nodded, he had gone on: “You are bloody well Brethon, aren’t you?” and though Aeden didn’t really have an answer for that one, he had been swiftly adopted, because the knight had lost track of his comrades in the Winter's Eve confusion, and was wandering forlorn amid the foreign revels.

He had heard enough to answer, a little absently: “Yes . . . well, it still wouldn’t work.”

“Why not?” Baerys asked, a touch too eagerly. “All your legionnaires are drunk, the walls of your city are barely guarded, a child could walk through the castle gates …”

Aeden glanced over at the legionnaires, grateful he and Baerys were speaking a different tongue from theirs. “And where would you come from with your bold army?"

“Well … say I was a chieftain in your north, one of the blue-painted sort your soldiers like to talk about …”

“One of the Druanni or Kadoli?” He pushed memory aside, and let his voice take on the lecturing tone of the tutor. “Say you were. Look up that way, Baerys. See Orison going north, way off that way? There’s another lake beyond that, Sacrifice, colder and wilder and dropped into the mountains the same way. And then the passes into the far north … suppose you come down that way, come down out of the high valleys and the prairie. Just above Sacrifice you’ll find the biggest fortress your Druanni eyes ever saw, big strong Caldmark, as big as this castle here and with some of the same Mandoran-built walls. It wasn’t finished by the Mandorans, and there was a time when the garrisons sent there couldn’t hold the place, a time when raiders would come down to Rendale … but that was hundreds of years back. Now it’s the kind of place you can only slip past with a few dozen men, if you’re lucky, and then what? Then you’re coming down along the lakes, with watchtowers and villages to see you, and regular patrols, and you just won’t make it, no matter how much we drink tonight.”

“Well,” the young Bryghalan said, “well, then, I’ll come down that way,” and he gestured up, up, toward the snow-mantled Guardians, and Aeden burst out laughing.

"Scale the Guardians? You don’t know what you’re in for, my friend. I've lived up there, summers, and nobody scales the Guardians."

“Really? Then where does the gold come from? The fabled gold of the Narsils, which persuaded so many of our fine lords to fight for you?”

“It comes down the gold roads. But the gold roads only go up, up, up — they end with the mines, and past them there’s only hawks and snowcats.”

“Well, then, the way we came in” — a gesture westward, toward the jagged Thornhills. “I’m guessing you’ll say that the fortresses we saw on the road from the moor, from your city of Mabon, will slow us down, but surely there’s some other tracks to take.”

“Not really. That road from Mabon you traveled had to be carved out of the rock by soldiers taking thrice-times pay, and it took two reigns to do it. There are paths for small parties, but not big armies. No, we’re safe from that direction too.”

“All right, then,” Baerys said, grinning, “I suppose I can’t beat your empire. I suppose Bronh meant for you to rule the north and Brethony as well, what with him giving you fistfuls of gold and a valley that can’t be taken from any direction unless the Unvanquished were to come riding north to do it. I suppose I’ll just have to be content drinking your ale, then, and thanking the sun in his radiance that you’ve deigned to marry into our kingdom instead of just conquering us too.”

I ought to be up here with a girl, Aeden thought. It’s Winter's Eve, I shouldn't be playing tutor to a knight who must have got his sword about a month ago.

Foolish to think of girls at all, though, when such thoughts turned inevitably to her.

“But you still have to tell me why it’s your empire anyway, your princess that we’re toasting. You don’t just have the talk, you have our Brethon look — Allasyri or I’m not my mother’s son. There must be a fine story in what brought you all the way here.”

If he was really going to Bryghala, this kind of question would be asked a thousand times. He needed a quick answer; no reason not to practice now.

“I was never Allasyri, not really, but my parents were. My father was a tinker, a metalworker, from somewhere in the west. He traveled, met my mother in Tessaer al-Yrgha, convinced her to go east with him, try life in the empire. We lived in Erona when I was a boy, then he got wanderlust again — wanted to see the Heart. We were in a party crossing the moors when raiders from the north attacked us. Maeonwy. They killed my parents, killed most everybody. I hid myself, until legionnaires from Northmark found me. They took me back, found me work — my parents had taught me letters, I spoke two languages — and then I came to Rendale with a leftenant assigned to the Falconguard. He recommended me to the Castle, and here I am.”

That wasn’t bad, dry and rote and quick, a rush of words that didn’t have anything to do with his real memories, the real sounds and smells and colors of that day.

“Bronh alive, and here I am joking about raiders sweeping down … Aeden, I am honestly sorry. A terrible thing, what a terrible thing …”

What he remembered most of all was how beautiful it had been, the sun breaking through after days of mist and cold, the colors of spring leaping out on land that had been gray and grim just the evening before. How blue the sky above his mother’s screams, his panting breath and burning lungs, the hollowed-out tor that saved his life. Just one lazy cloud, lazy and sheep-white and completely unconcerned.

Baerys was passing something to him now, a flask that he took and drank from, tasting not the expected ale or Kiorssan brandy, but some odd peach drink from Brethony. Odd but not bad — and he sighed and gulped it down, leaning back into a mound of snow and staring up at the wheeling stars and the bright firecrackers.

“. . . make it up to you. And your hospitality — I appreciate it no end. When we get to Aelsendar, I promise you, I’ll take you out drinking, wenching, that sort of thing— even with the odd accent your Brethon’s bloody wonderful — we can have a grand time. If you like. I mean, you'll have your people, of course, but it would be good to get away from the other fellows — being around knights can wear you down, especially when they're all fifteen years older than you and think Prince Maibhygon’s the sun god made flesh. Not to speak ill of the Prince, I just don't know him that well . . .”

Aeden took another drink, swishing the liquid around his mouth, and leaned up on an elbow to regard his companion. “You know, you're an odd sort of knight."

Sire Baerys' face fell for a moment. “It comes of not being supposed to be one, I figure — my father was knighted on the field, back when we Brethons were busy fighting each other instead of busy being conquered, so I wasn’t brought up as a real lord’s son would be; he didn’t know how to do that. And I’m new-minted myself, anyway . . . nine months a sire, and they send me with the prince, because of my father, I suppose, him having saved the prince’s uncle’s life. Give me another five years, though, and I'll make a proper knight, I give you my ...”

He broke off as Aeden tossed a handful of snow at his face. "You’re fine, just fine.”

“Glad you think so,” Baerys said. “Glad somebody thinks so. And you’re fine, too, Aeden — not that I really know you, but you seem like a grand fellow.”

"Why yes. Yes, I suppose I am at that,” Aeden replied, and lolled back, draining the flask and feeling the unhappiness seep out of him a little, as a soldier cursed and another rocket flew upward and split the sky with light.

The dice games had broken up at last, the chicken race in the garden had ended unsatisfactorily, most of the people left in the great hall were asleep, and Padrec came down the steps to the bailey with a piss building in his bladder and a wobble to his step. A few hangers-on followed, iron drawn to a princely magnet, but he was trying to ignore their drunken flattery, and trying as well to ignore the fear that Aengiss was right about the plot but wrong that they had time, and that one of the lordlings following him might knife him if he wandered too far from the revelry and lights.

There was still enough of both in the courtyard, where the crowds had thinned but bonfires still burned, and the steam of a hundred breaths still floated, and the colors of the rainbow still exploded high above. It was warm and cold at once — the chill of the deepening night freezing the slush that warmth and pounding feet had melted, the air going from hot to frigid instantly if you stepped close to a bonfire and then away. Fire and ice, fire and ice, he thought, a little disoriented in the smoke, recognizing a few of the faces, sensing the hangers-on still at his heels. His eyes smarted close to the fires, and when he stepped backward he slipped on a patch of newly-frozen ice, went down, felt hands grasping at him and lashed out, reflexively —

— “Prince Padrec!” A young woman shrieked, fending off his flails and drawing him up toward her bosom. "Do you remember me, Your Highness? It’s me, Dwen!”

“Dwen …”

“Gerdwen, Prince Padrec? I’m Lord Renwell’s daughter?”

“Lady Gerdwen,” he managed. The daughter of the earl of … Merdholt? A keep on the edge of the Fens, where they had broken their journey to Sheppholm that summer? Yes, that was it — and hadn’t Dunkan had his way with her, or she with him …?

“Are you all right, Prince Padrec?”

“Yes,” he said, as the followers trailing him met the group around her, a small crush of minor nobility — “yes, of course, my lady. Just a fall, I’ll be fine.” He cracked a smile, trying to meet her eyes instead of addressing the breasts spilling goosebumped toward his hands. “I might have had a drink too many, Winter’s Eve and all.”

“Oh, we’re all drunk!” she cried happily. “Call me Dwen . . . we’re all drunk here!" Her arms swung out, embracing all the shapes around her, who laughed with her and shouted encouragingly and unintelligibly.

There was nothing for him here, the Aengiss voice in his head told him — no political advantage in flirting with a trollop and her friends, only risk in drinking all the way to the dregs of the evening.

Dwen caught at his jacket, her snub-nosed face looking up hopefully at his.

"Would you like to climb up and see the fireworks, Prince Padrec? They're ever so lovely, and we're all going to climb the towers and see them …”

Her breasts were pressing against his lower chest, insistently enough to make him feel something further down. His hand went to his own breast, to Caetryn’s letter. Nothing for you here, Padrec …

But angels, he was tired of listening to that voice.

“I should love, my lady, to come and see the fireworks,” he managed, with an approximation of a courtly bow.

“Well, grand!” she shrieked. “The prince is coming! Everyone? D’you hear?"

Then another form loomed up in the smoke, coalesced, became Paulus bar Merula.

“Damn, old man, I've been looking everywhere for you!”

“Well, here I am!” Padrec said, playing at happiness, clapping his friend on the shoulder. “I lost you at the dice game …”

“Yes, here you are, and what do you think you’re doing?"

“Doing?” He glanced at Dwen, who had stepped back to stare admiringly, as women always did, at Kander-on-Tarcia’s earl. “What are we doing, my lady?”

“Going up to the towers!” she cried. “Do you remember me, Lord Paulus? Will you come with us as well?”

“That’s right,” Padrec agreed. "We’re climbing to see the night’s last fireworks. Care to come, Paulus?”

His friend swept a tangle of black curls back from his forehead. “Another time, another year, another life, Padrec.” Then he turned to Dwen, slapped a quick kiss on her hand, apologized for the inconvenience, and pulled the protesting prince away, back through the crowd, back toward the shadows of the keep.

“What’s the bloody hurry?” was all Padrec managed until they were inside. A few of the torches on the great stairs had burned out, and the two young men stumbled up the flight, past the huge double doors of the feasting hall, down another hall and another, with Paulus speaking all the way.

“Aengiss sent me to find you …”

“He’s still awake? Tell him I’ve had enough of him tonight …”

“… sent me to find you, had a damnably hard time doing it, let me tell you. You shouldn’t be out, not tonight, old man. Ought to be in your bed by this time, and I should be — instead I’m off finding you. Should have sent Dunkan, except he can't be trusted with much except bedding and fighting. Where’s Elbert when you need him, I ask you! Here I am doing everything myself . . ."

“What in Gabriel’s name…” the prince managed as they reached the stairs leading up toward the imperial apartments. “What are you going on about? What is Aengiss afraid of? What is he playing at?”

"Playing at?” Paulus grinned. "Listen, I’m sorry, I know you’re to keep out of it, so keep out of it. Get to bed, get some sleep, hope you don't have a hangover … tomorrow will be a new day.”

“A new day?”

His friend gave him gentle shove up the steps. “Tomorrow and all days to come!”

“Wait! What the hell are you talking about, Pauli? What does Aengiss have you hunting? I’m your prince, tell me.”

“Shh.” Paulus raised a finger, placed it across Padrec's lips, and leaned up to kiss his cheek. “I always thought we were just comrades, Adjutant Montair. But fear not: your loyal servants will make a report to you when the time is ripe. And the time will arrive sooner if you sleep now — and don’t make me carry you up to bed myself.”

The prince met his friend’s eyes, darker than the darkness, and said with some fervor:

“Well, fuck you all, Paulus.”

Then, temporarily satisfied, he turned and staggered up the stairs to bed.

It was strange to walk the Castle so late. Fidelity had walked its halls in twilight but never in such darkness — the torches guttering, the firepits burning low, the full of night gathering in doorways and alcoves and stairwells, trumphant wherever firelight failed. It was even stranger to walk in the last hours of a revel: All the formality of daylight was swept away, the performance of power and nobility that even stewards and servants and messengers always seemed to offer one another, and the stage instead displayed a pageant of misrule. The rooms rang with shouts and laughter, the corners held embracing lovers and merry bands roamed the hallways, while here and there were sleepers like corpses, splayed out in the last abandonment of drunkenness.

Like corpses was a morbid thought, but also a dream-like one, because the whole scene was easy to reimagine as a vision of the aftermath of battle, of the Castle conquered and sacked: Instead of drunken sleepers, dying soldiers; instead of celebratory noise, calls-to-arms or shouts of martial triumph; instead of rockets going off outside and above, catapults hurling fire down on the towers — and in the flickers of firelight, a hint of the flames that would consume everything when the sack was finished.

In which case she and her sisters were like an armored forced moving through the chaos, their robes and veils like chainmail, too daunting for any looter to approach.

She was used to such dream-like feelings now. Since that night at the Snow Goose her sleep had been haunted, and since her last night at the House of Birds the dreams had become consistent, strange, intense. Often she saw her father, dead or living; lately Father Aldiff, on his bier or at the altar or unexpectedly on a bridge or in a clearing in the woods; sometimes Hilwen, always just beyond her reach; sometimes her mother; sometimes Jophiel Themself. And then there was the great citadel — sometimes glimpsed at a distance, through a window or in the background of a picture or briefly in a reflection, and sometimes rearing up before her, both its whole and ruined forms so vivid and familiar now that she half-expected to see it in the waking world.

Indeed even now as they reached the chapel doors, halting while Sister Recompense unbolted them, she wouldn’t have been surprised to see the great dome rising above the altar and seraphical, the frescoes and stained glass, overshadowing the chapel …

But all was as usual within, except emptier and darker. A few of the sisters went to light tapers and slowly light bloomed around the altar, spreading to unshroud a few of the statues, Zadkiel and Raguel and Uriel, while the sisters passed together to take their places on the altar’s left.

As they filed into the benches a rocket burst somewhere up and above the chapel roof, and its flare of light illuminated the rose window, illuminated the whole chapel for an instant, like a mystic’s fleeting vision in the midst of the darkness of this world.

Recompense had locked the doors from the inside, sealing the revelry (the battle) outside, leaving them alone. Without speaking they all unveiled as the choirmistress took her place before them, beside a single red candle rising almost to her height. Then she unveiled as well, revealing the kindly eyes, the bulbous nose, the wisps of white hair along her cheeks.

“The prayer, sisters,” she said, her gentle voice carried back in echoes.

They spoke the ancient words as one:

Iestifira coreda, iestifiri araphaca, coredis, coredicala. Vestris’a, Inagali. Vestris’a, Mithraelis. Coradathis’a al, castabis’a il, vosevis Unafori. Vosevis Abadonis. Vosevis suspimi agor.

Save us from the Damned. From Abaddon. From the final dark.

The dark was indeed all around them, pooling and eddying. The darkest nights of the year, given especially to the Damned and their devils, as their time to prowl the world in search of unwary souls. A blur of scripture and legend, a reason to say your prayers with special vigor, to seal doorways and mark lintels with the ashes from the sacrifice — ashes that were handed out in great spoonfuls after the service by the huge-bearded priest, standing outside in the marketplace with his cloak billowing under the stars, memories from a dozen different Winter’s Eves in the days when she was still Rowenna of Balenty, and invisible devils were the only ones she had to fear.

But now it was time to sing against them, against all the devils and the dark. Recompense raised her hand, the kindly smile gone, all seriousness now, like a serjeant before a battle, a diver just before a plunge.

“Now, sisters. Now. Now let us begin.”

It was long past midnight and the revels were finally fading into sleep, but Edmund stood wakeful at his balcony, watching the last rockets spill their fire across the sky while the last songs and bonfires died away and the night came rushing in to claim his castle. He was sober, which was striking — he had been slightly drunk at dinner, and then that had worn off, and he had expected to drink again; but the bottles stood untouched on the table and his mind was clear and unusually untired.

The Emperor of All Narsil paced to the glass and stared at himself, or at least the self that candlelight revealed: a tall, gaunt figure, his hair sparse and gone gray, his cheeks sunken, his eyes tinged with red. Not the dashing figure he was once — but then, he didn't need to be dashing, did he? The time for wars, for galloping madly about, leading men through fire and ruin — that time was mercifually over. This was the age of the peacemakers, and he was the first of them.

Are you happy, Alsbet? he had asked her, before the feast, and she had glanced at her husband-to-be and smiled what seemed to Edmund such a smile.

Yes, Father, very happy.

That was all he could ask for, in the end, was it not? To see his daughter happy, and peace on the land, and to know that he had done what Bryghaida would have wanted. Yes, how Bryghaida would smile, if she were here — but he would be with her, soon enough. He had done what was necessary, and now he could go to his reward content, and even Padrec would understand in the end that he had done the right thing, the necessary thing, no matter how unexpected it had seemed.

Yet somehow, for the first time in years, the idea of slipping away into a peaceful death held no appeal. It was peculiar, this sudden clear-headedness that had seized him, and he did not know what to do with it. He paced his chamber with restless energy, and then stalked again to the balcony and stared out into the night — at the stars, and the Castle’s towers, rising like gloomy sentinels. He was seized with a sudden urge to be higher than he was — perhaps he would climb one of the towers, climb and look down on the world as the Archangels must from their seats in the heavens. It had been a long time since he had surveyed his castle and city. It would make him feel — well, like an emperor. Like what he was.

There was a soldier at his door, one of the Falconguard, but the poor fellow was asleep and Edmund took pity and did not wake him. There was some faint noise behind him in the imperial chambers, like a door creaking slightly, but he barely heard it as he pulled his ermine-trimmed cloak around him and moved off down the hallway, letting the pool of late-night quiet filling up the Castle swallow him as well.

In his bedchamber Padrec dozed, then woke as he sometimes did after drinking, his mouth dry and his head in pain. He rose to look for water, found his pitcher empty, and then pulled the bell for a servant — only to remember that this was the one night of the year when the servants were excused from answering.

He thought of going down the kitchen himself, but the strange encounters of the night made the long walk through darkened corridors seem too fraught to contemplate. Instead, taken by what felt like inspiration, he went to his own balcony and found the uncleared snow from the evening’s fall, which he cupped and ate in heapings, like a child in his first winter.

As he crouched half-dressed, relishing the cold powder on his tongue, a faint sound of singing reached his ears — a haunting sound, women’s voices mixed and overlapping, thin and distant like the sound of a lamenting ghost. He rose and looked out and down, and then realized that he was hearing the blue sisters keeping the first night of their Great Vigil, singing for two full bells as they would for each of the next four nights — singing against the darkness, against the Damned, against the terror that came on men in the small hours of the year’s most tenebrous nights.

To Padrec, there was something stirring in the sound, something embattled and brave in a way that reminded him of warfare — but in a female key.

Which reminded him of the letter-within-a-letter that he had left inside his coat, now cast aside and crumpled on the floor.

He went inside, collected the garment, found the letter. One taper was still burning, enough light to read by. He broke the seal eagerly, plucked out the parchment, recognized again Caetryn’s handwriting, this time using his language instead of hers.

Remember us, my prince, my king, now that you are come into your inheritance.

Remember Brethony.

Remember the greater kingdom yet to come.

Fidelity was last in the long line as they left the chapel, everyone abuzz with a strange energy, but with exhaustion waiting as it ebbed. The darkness they had sung against was everywhere, and the Castle mostly lay in silence now, the aftermath-of-battle feeling drowned in sleep.

They were turning a corner in the great hallway when her robe caught and she stumbled a little bit, falling a few steps behind Temperance and Gravity. As she recovered her balance there was a sound behind her, a soft moan, like someone sick or in pain. She turned back and the sound rose again, a woman’s voice she thought, and she went a few steps back the way they came before she saw the girl in what looked like servant’s garb lying hard against the wall, just inside a circle of torchlight, her head twisted at a dreadful-looking angle, with some sort of dark spill across her chest.

For a moment her inner eye saw her father’s corpse with its bib of blood, and she hastened quickly over to the girl, dropped to her knees — and immediately gagged a little, because the dark spill wasn’t blood but vomit, a dark green pudding somehow heaped between the girl’s upper lip and upper bosom, with each breath or moan taking a little of the vomitous pudding up into her nostrils.

Fidelity took the girl by her thin shoulders and tried to prop her back up, and gathering the sleeve from one of her limp arms she dabbed at the vomit, trying to clean it from the mouth and neck and cleavage. Then she turned to call for help from the other sisters who couldn’t be all that far away, just around the corner, hadn’t Temperance noticed she wasn’t with them anymore …

That was the moment when the torch above her fizzled and went out.

He was no longer as fit as he had once been, Edmund realized as he wheezed his way toward the top of Matheld's Tower. His bones ached with the cold, and his lungs and muscles ached more from the endless stairway that circled inside the spire like a serpent tunneling to reach the world above. It was dark on the steps, too, with torches burned out and no one to relight them, not on this night — and he had stumbled twice, scraping a knee and sending a volley of curses into the silence around him.

No one heard him, not this high; there were chambers crammed with guests in the lower part of the tower, but the last fifty spans the tower tapered until there were no rooms, only stairs and torches and windowslits.

“I should have picked another tower,” he said aloud, hearing his voice reverberate strangely as it skittered down the steps, away into the darkness. “I should have picked another . . . a lower tower!”

But he had wanted to be alone, and the other towers were too filled up with people, their stairwells likely still crowded and their rooftops probably still occupied by lovers. Well, maybe it was too cold for lovers, but they had set off fireworks from Burnt Tower, and he had no desire to share his view of Rendale with sleeping soldiers and piles of unused rockets. No, better to be alone, so that he could gain ... perspective on the world.

The emperor of All Narsil came around a last bend and the heavy door appeared, with a single candle flickering and bobbing beside it, miraculously still alight amid the breezes that coursed through cracks in the centuried stone. With a grateful sigh Edmund pulled himself up a last few steps, thrust open the portal, and stepped out into the cold that ruled high above his Castle.

Matheld’s Tower had a pointed roof that prodded at the sky, and an open gallery circled the tower just below the eaves. There was a stone railing, sturdy enough to prevent the foolhardy from imitating the tower’s namesake and pitching themselves off, although it was cracking in places, Edmund reflected as he made his way around, his boots making prints in unmarked drifts of snow. There was ice, too, black on black stone where the snowdrifts parted, and the emperor slipped briefly, grasping for support, his breath coming in quick puffs of steam. It was so cold this high, this late in the year, and as he looked down on his city he shivered, wishing for something to wrap around his ears.

There were still lights burning in the snowy miniature of Rendale that spread below him, enough to trace the outline of the city, its streets and houses running disorderly down to the waters of Lake Orison. It was a good city, he reflected, though he had spent little time in it these last few years. But it was still a small city, and not only because he stood five hundred spans above — small and patchwork and provincial, not a true imperial capital no matter how you looked at it.

If it grew as it had grown for centuries, someday it might rival the other cities of the empire, at least. But why wait for that? This was the time of peace, a peace he had made — what better to do in peacetime than build? The idea was strangely exciting, and Edmund looked down and imagined it, imagined high stone walls surrounding the city, streets paved with rock quarried from the Guardians, new buildings going up, the city gleaming in the summer sunlight as an imperial city should. Why not? Why should all those other dukes, especially the ones who had behaved so badly at his table — Cresseda, Cathelstan— why should they have fine buildings for their cities while Rendale sat shabby beside its hulking Castle?

“Why indeed?” he said sharply, making his way slowly along the railing, now looking down on the rest of his own seat, the great half-Mandoran sprawl of stone. What if he were to simply tear it down as well, tear down Burnt Tower and the wind-scarred walls and even the central keep, the old Mandoran con, and replace it all with a palace, a fit seat for a ruler whose empire was, at long last, at peace? He could do it — he had made an end to the wars, the conquest, and surely he could do this, as well. It would make Bryghaida proud, would it not? And her garden would remain, but as the seed of a new garden, a vast park inside the new palace, with beautiful flowers in the spring …

“I am still the emperor,” Edmund said, feeling the air burn against his skin, feeling invigorated. “There are yet things that I can do.”

Someone laughed, an unexpected sound in the winter dark, and he spun to see a figure sitting on the stone railing just a few spans away, his legs crossed and his back to the yawning fall. For a moment horror filled him as he glimpsed the distorted head and the weird black-and-white pattern on the stranger’s face — and then he realized that it was just a fool, just one of the fools his chamberlain must have hired for the occasion, the pattern face-paint and motley, the misshapen head just a jester’s cap …

“You frightened me, sir,” he said weakly.

The fool spread his hands. “My apologies, mighty emperor. It was not my intention.” Then he laughed again, a high-pitched and mirthless sound.

“Cold up here, isn’t it?”

“Yes, Your Majesty, very cold.”

“Are you safe sitting there? You won’t slip?”

"Oh, it’s slippery indeed. But I shan't fall, oh no, I shan’t fall, not at all, not at all."

He would speak in rhyme, Edmund thought irritably. "I would think that you would want to be asleep now, master fool."

"I might think the same of you, master emperor."

There was a mockery in the fellow’s tone that he did not like. A fool could say things that other men could not, but still … “Well, yes, I suppose,” he said. “I came up here, to be frank, to be alone — alone.”

The black-and-white face blinked innocently.

“Alone,” Edmund repeated. “I know you were here before me, but I wish to be alone now.”

“I am dismissed, great emperor? But I’ve traveled far to be here. So very, very far.”

There was something here that was not quite right, Edmund thought as the wind whipped up, keening in his ears, searing his cheeks …

-- his bells aren’t jingling, the wind is burning my skin, why don't the damn bells move?

“So far, so far …” The fool’s voice was a melancholy sing-song, now. “How many leagues to the white queen’s tower? How many spans to the red lady’s bower? How many roads lead into the black? How many travelers never come back?”

“I’m too tired for riddles,” Edmund said, still watching the bells.

“Too tired?” The sing-song stopped, the voice became casual, drawling, a bored aristocrat stifling a yawn. “Well, then I hope you’ll at least compliment me on my accent. Learning another one of your languages is a horribly tedious chore, and I tried to demur, you know — I said it would be more impressive if I was utterly incomprehensible to you. But he didn’t listen, he said you had to understand me, he made me clutter up one of the best rooms in my memory palace with all – sorts — of — ugly — furniture. So I do hope you’re pleased.”

“Pleased with …?”

“With how much I sound like you, of course! How perfectly and uncannily I’ve captured your dreadful mortal accent.” And suddenly instead of the bored drawl the fool sounded like — well, to Edmund he sounded almost exactly like his own father, Cedrec, dead for fifteen years.

Whatever this was, it was enough. “Save your sport for the feasting, jester,” he said, and made to go past him to the door.

The fool pushed down against the parapet and catapulted himself upward in an acrobat’s flip, landing with perfect form between the emperor and the opening to the stairs. A white-gloved finger, too long for its hand, waggled in Edmund’s face, and the emperor stepped backward, his hand going reflexively to the sword he no longer wore.

“Sport? You think this is sport? No, oh mighty emperor — if I just wanted to sport with you I would do something like this …” and now the voice was low and throaty and obscene, the voice of a torturer in the deepest dungeon in the world, and the painted black-and-white face seemed to roil in the starlight as if there were worms or snakes beneath. The eyes went from dark to a brilliant, uncanny green, and Edmund drew back, prayers coming unbidden to his lips, a rattling invocation of the angels ....

“Yes, pray to your high-in-heaven princes,” the thing said, because it was a thing now, not a person, not the jester’s form that it was temporarily occupying. “Pray to those arrogant ponces, those golden snobs, and see if they come down and help you. I don’t think they will — too proud for it, that lot, too high and mighty. Whereas we have always helped, we have always been ready to assist — provided the terms are right, of course, and the compact appropriately made …”

“… what … what do you want from me?” was all the emperor could manage, half-aware that his back was now against the parapet.

“Want? We just wanted you to know, your imperial majesty. We wanted you to know that you will never build your monuments, oh mighty emperor of nothing . . . never never. No, you will be called Edmund the Fool, Edmund the Idiot, Edmund the — ”

“Stop!” The fool's voice had reached an impossible pitch, a terrible whining sound in his ears, and he clapped his hands over them, trying to shut out the sound, make the nightmare break.

“Stop? Did you stop at Naesen’yr, or Wyr'daen, or Tessaer al’Yrgha? No? Well, this is the price, this is the cost, this is the wheel turning and grinding you to bits. You, Edmund the Drunkard, Edmund the Wife-Murderer, Edmund the Failure…”

I am dreaming, Edmund thought. I am dreaming I am dreaming I am dreaming.

“Ah, but the world of dreams is ours,” the fool said. “The road of sleep goes under the hill, the court of dreams has a silver queen, and all the phantoms of the night are painted gold and blue and green …” His eyes were gold now, and the sing-song became the drawl again: “A loose translation – I’ll have to play with the rhyming scheme, I think …”

“In the name of all the holy angels … In the name of Mithriel, disperser of demons, I bid you …”

“But I’m not a demon,” the fool told him. “I’m just a simple fool, really, with a few illusions up my sleeve. Can I show you one of my tricks? Just one? Then I’ll depart from you, I promise. Let me just play fortune-teller for a moment, and give you a glimpse of the future — a future that, I’m very sorry, you will not live to see.”

“In the name of Raphiel,” Edmund tried again, trying to gather the will to bolt, to stumble to the door and slam it behind him and stagger down the stairwell to where the wind did not howl and the fools were human.

The creature flicked a white-gloved hand. “You only have to look behind you. It won’t bite you. I promise.”

He looked.

For a moment he thought that time had rolled back a few hours, that the revels of Winter’s Eve had somehow been renewed. But then he realized that everything was different — the sliver of moon had become a full one, shedding a bright and brazen light, the snowfall was deeper, great drifts burying the battlements, and the bonfires and torches were somehow in the wrong places … and then he realized that he was looking at a ruined version of his castle, the chapel windows shattered and the walls breached and the gate fallen in … and then below the city was burning too, great fires raging in the lower quarters, the dome of the temple cracked, shadows moving everywhere and screams rising with the smoke …

“A fine sight, isn’t it?” the fool said, seated again beside him, kicking carelessly at the parapet. “It gives a good light, your city. But no, no, don’t turn from it — ” and his gloved hand seized Edmund’s arm, a grip as inhuman as the rest of him, and held the emperor at the parapet, forced him to look again down on the snow-mantled ruin …

… except now the fires were lower, the ruins starker, the screaming done, and there was a strange chanting rising through the winter air instead. The castle’s courtyard was lit by a single great bonfire, and there was a crowd moving — dancing? — in a circuit around its light. They were costumed and painted and some of them wore horns – though he should not have been able to see the details from so high up, which was surely proof this was a dream, a shred of hope to keep him from tipping into madness — and they carried something, no someone, the way he had been chaired on the river, someone seated on what was almost a throne, except they were bound upon it, bound and also crowned, with flowers or antlers or both, and they were being hoisted up, up, to a place prepared atop the bonfire, and the gag was off and the hair spilled free and Edmund could see who it was and he screamed, a wretched sound, as the flames billowed up and she screamed as well, atop the pyre, but not from pain so much as terror at the something, the awful Something, crowned as well and cloaked in fire and shadow, that stooped to kiss her as the bonfire claimed them both …

And somehow — a dream a dream all a dream — though the chants were in a different language, a language like Brethon but also different, he could understand them perfectly, understood the meaning in their pulse.

The king

The king

The king has come

has come to claim

But Edmund listened to no more. He wrenched himself away from the parapet with all the strength he had, and looking wildly around the towertop saw nothing, no one, no fool, no monster, nothing but the snow and stone. Not daring to look down again, to see if the vision below had disappeared as well, he flung himself at a staggering run toward the door, pushed it open into the yawning stairwell, and stumbled through — into the arms of Paulus bar Merula, who came out of the darkness and gripped the emperor’s shoulders with both hands, so that together they moved backward out onto the balcony, back into the frozen night.

Colliding with his son’s friend, with the hard fleshly reality of the young nobleman, gave Edmund an overwhelming surge of relief. “Paulus,” he breathed. “Lord Paulus. Thank the angels. It wasn’t real. It wasn’t real.”

Paulus’ beautiful dark eyes locked with his, and the younger man smiled sadly. Edmund opened his mouth to speak again, but before he could the lord of Kander-on- Tarcia leaned forward and kissed him on the forehead.

“None of it is real, your majesty,” Paulus whispered. Then he drove the emperor backward to the railing, his spine hitting the hard stone as the young lord bent to lift and heave his sovereign up and over the parapet, Edmund’s cloak billowing out like wings as he fell, clawing at the air, unable to even cry out, his wife’s garden rushing up to meet him as his mind reached for Bryghaida and his body shattered on the flagstones, beside a rosebush that would bloom with the spring.

There was silence everywhere in the Castle. Then the snow began to fall again, softly, as if in benediction.