The braziers that ringed the practice yard smelled ghastly all morning and when the fog had burned away and the air had warmed sufficiently, Padrec ordered them extinguished. One of his pages, a thin, freckled boy named Lammen, fetched water from a well in the east bailey and poured it over the flames, sending a curtain of foul smoke rising into the winter sky. The sun climbed high and hot overhead, and the snow melted off the ground and the headless, ivy-mantled statue of Prince Edgeren that watched the practice yard, while Padrec sweated and stripped until finally he fought shirtless as morning ran into afternoon and the Castle waited, its walls and towers ringed with anxious watchers, for tidings from the north.

He sparred with his soldiers, the few men of the Falconguard who had been left behind to guard his life while their comrades fought to save his empire. Padrec’s imperial person presence seemed to awe them into silence, but they fought well, their wooden blades thudding against his, and that was all the Emperor of All Narsil wanted on this morning.

Well, not all. He wanted to pick up a real sword and lead an army into battle — to smell blood and hear the sounds of war again, and to see his enemies fall before him, see the traitors die. But this was not permitted.

My father led armies, he had protested to his council — to Aengiss, really, for Aengiss was the only man who mattered now. I rode beside you in Brethony. Why should this be any different?

He knew the answers, of course. Because they were outnumbered, fighting for the survival of his throne, not the conquest of his enemies; because he had no heir, his brother was far-off and his sister and his uncle fought against him; because even his father had deferred to Aengiss, the great war leader, the terror of the Brethons, the man who had never lost a battle. And above all because this was a great gamble, meeting the rebels in battle outside the walls, and should the gamble fail Rendale and even the Castle would likely fall without a fight, and if it came to that he would need to be well away, galloping south, risking whatever waited at Aldermark or beyond. Leaving him behind was a way of choosing both doors, both options, fight and flight: The Falconguard would fight, and he would wait and be ready to flee if riders came down the lakeshore with news of their defeat.

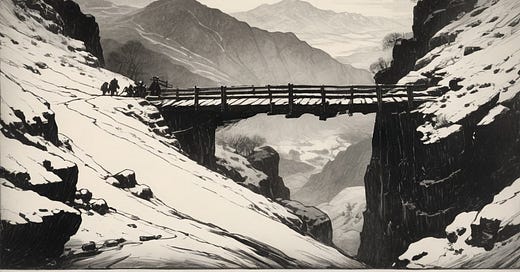

So yes, he knew the reasons, and he had acquiesced and remained while the Falconguard moved north late the previous afternoon, later than planned because of his sister’s miserable betrayal, but still early enough to make all of Aengiss’s preparations around Dernbridge, the surprises that would win the day if all went well.

If all went well. There it was, the hope of every commander, the whispered prayer of every clever tactician and fearless captain and superstitious soldier on the night before battle, before the long midnight when sleep did not come and the rustling sound of the dark made a man start up, certain that they were here and that they, the silent enemy, would kill him while he slept. And then they did not come, the wind laughed and said softly we will have you . . . we will have you . . . you will be ours tomorrow.

Now tomorrow was today, and Padrec swung his sword and looked down to watch his muscles ripple, and it occurred to him that he was turning soft, that there was flab and gut and sag where he was used to a satisfying suppleness. He didn’t even wear the crown and yet he was growing soft under it already. He found himself thinking of what Caetryn would think if she saw him, if she would be disappointed, if her ambitions for him — not her desire, there was no sign of her desire, he pushed that thought away – imagined him a certain way, the young prince riding to war, not the fleshy pale emperor hiding in his practice yard while Aengiss fought his battles for him.

It was folly but still he wished that Cat were there, on the walls with the other ladies, with the ambassadors and noblemen to old to accept Aengiss’s “invitation” to join the battle — all wishing themselves far away, no doubt, all waiting for a glint on the northward highway, for the thunder of Veruna’s horse.

In his mind’s eye he saw them coming, all through the foggy morning and unseasonably warm afternoon — men in the tabards of the empire, but not his men, coming down the lakeshore, surging over the Castle’s walls like a flood, and he swung his wooden sword and drove his sparring partners back, while the snow melted and fires danced in the smithy, and the headless statue watched him from the west end of the yard.

The sun had passed its low midwinter zenith when the shouting began on the walls, and though Padrec was frightened he tossed his sword away and went to greet the men who came riding down the highway — men who shouted victory, he realized with mounting joy as the postern door was flung open and Dunkan burst in, with other men behind him, and shouldered his way through the crowd to grab his emperor around the neck and face and shout —

“We fucking did it, Padrec! The tricks bloody worked, we turned their flanks and buckled their center, and some of the bastards didn't even fight, and Veruna’s dead and Benfred, and the whole damn lot of them are surrendered or scattered . . . we won, by all the Damned and the Archangels too, we fucking won!!”

There were cheers and more embraces and songs, and the bells of the city began to ring, great joyous peals from the temple and all the little shrines, washing over them as Dunkan told him what had happened, how the men hidden in the village had taken them from the rear and the catapults had worked and Coallen of Ysan had led the charge and Aengiss himself had cut down Dethferd Rendell, and how Mulias bar Sedura wouldn't fight and was begging for mercy, and his men were all prisoners, and so were most of the rest of them, and the others were dead except for a few hundred who took to the hills, and they had won, Rendale was safe, his crown was safe!

Padrec was closer to tears than an emperor could acknowledge, and he shouted to Dunkan —

“What about my sister?”

His friend blinked, as if he hadn’t even thought about the issue, and then replied that she might have fled, but he thought that Paulus had taken some men after her — and that no one could get far with Paulus on their scent.

It was winter, the sky was already growing dark, and the first fireworks blossomed above Matheld's Tower, red and green sunbursts against a deepening blue.

They rode north all that afternoon, along the churned-up highway where Veruna’s army had tramped southward the previous night. They had left their lakeside vantage point when the battle was lost, when they could see the soldiers begin to flee or surrender, and there had been no immediate signs of pursuit as they galloped away north. But Paulus was still out there, and Alsbet was certain that he would have men after them within a few hours, dozens of soldiers with fast horses and sharp swords to cut down her men, the way he had killed Veruna, and her father, and angels knew how many others, all the while wearing that awful, contemptuous smile.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Falcon's Children to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.