From the infirmary she could hear her sisters singing.

The room was not large but compared to the sleeping cells it was palatial: Six beds, as many tables, and then a long low bench heaped with cloths and bandages, with a pair of ewers and three basins stacked inside one another at one end. There was a wide window, like the window in the refectory two stories below, but facing south instead of north, looking out over the roof of a neighboring apartment and on across a jumble of peaks and towers, the city spilling downward from the sisterhouse’s Castle-shadowed perch.

The chapel’s ceiling was just beneath the infirmary floor, and the chanting rose through beams, plaster and the reddish tile beneath her bed. The same prayers she had sung with Temperance in the harbor shrine for Father Aldiff, but perfected, faultless, with Devotion’s harmonies spiraling at intervals. Rehearsal, practice for the imperial funeral the next day.

“You know, I was sick in this room for two months once,” Reverend Mother Concord said from where she stood, looking out the window, the high blue crown above her cowl matching the chimneys rising in her line of sight. “Sick with the yellow pox, the year before Princess Alsbet was born if I remember right. Just after I took my final vows. Half the sisterhouse had it, ten sisters died. Maybe more — twelve, thirteen? I don’t remember. A few like me were sick and didn’t die, but didn’t get better either – for weeks, months, more. I wasn’t the longest abed — that was old Sister Patience, dead these seven years. But not dead then. The day came when she walked out of here, scars all over her face, cheeks sagging off her bones. Blessed angels she was a sight. But she was alive, and how we cheered for her when she came for her first meal. How we cheered.”

The Reverend Mother turned to her, with her own sagging cheeks, her own faint line of yellowed scars above her owlish eyebrows, her kindly eyes.

“That’s the sort of place the sisterhouse can be, Fidelity. I hope you know that, by now. Doesn’t matter where you come from. How you came to be one of us. We really are bound together. Jophiel really does watch over us. When one of us suffers, we all suffer. When one of us is healed, we’re all healed. When one of us strays, we all feel it.”

Fidelity was trying to listen, trying to seem tractable and innocent, but the weight was still in her stomach, the heaviness of it, like a ewer she had meant to drink from and somehow accidentally swallowed. The nausea was gone, at least — after her performance that morning there was nothing left, everything she’d eaten for two days had painted the refectory’s floor. But still she didn’t feel cleaned-out as one usually did after purging in an illness. Her belly and her bowels were empty, but she was still carrying the weight.

“Child,” Reverend Mother Concord said, coming to the foot of her bed. “I just want to make certain that you’re happy. That you aren’t carrying any burdens in your life with us.”

Fidelity managed a wan smile. “Oh, Mother, no, I’m still so grateful to be here … I’m just sick, that’s all, just sick, I’ll be better, I’m just sorry to let Sister Recompense down for the singing …”

The eyes were kindly but unconvinced. “I spoke to Sister Excellence, she doesn’t see any sign of illness. I can send for a red sister to examine you, but I’ve seen my share of girls, I’ve seen worse than what you did to the refectory, believe me, and I’ve seen it come from nerves, often enough. And my task is to look after you, as I promised the Lord Chancellor. I know you wandered off on Winter’s Eve. Got lost they said. I told Sister Diligence not to punish you, I don’t think you were up to any mischief, but then this. Then this. So I came to see you, Sister Fidelity. Came to see you, my daughter. Just to see if there’s anything troubling you.”

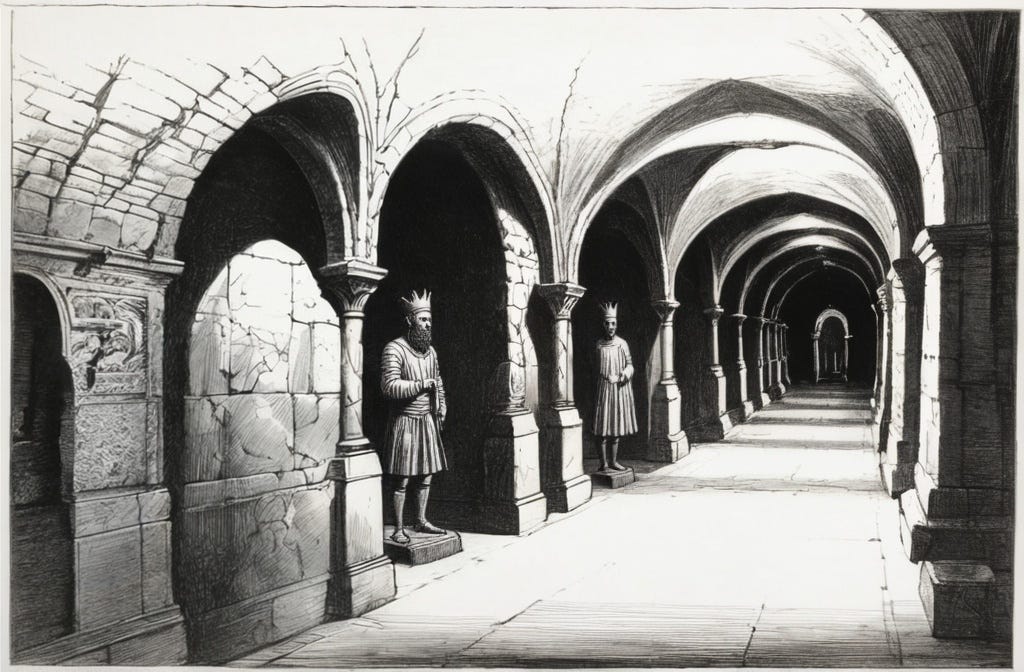

Wandered off … She hadn’t wandered, really, she had just tried to help the poor drunk girl, it was only once the torches went out that she had found herself lost. And even then she hadn’t been wandering but searching, searching for the way to the stairs that her sisters must have taken, searching for the party that must have been dispatched to find her — that did find her, eventually, a stern Diligence and an anxious Temperance and several others, finding her where she had ended up, back at the doors to the chapel, huddled in their shadow, turning over what she’d seen but not yet clear on what it meant, carrying a mystery but not yet carrying the weight.

“Mother,” she said now, her eyes still drawn the older woman’s yellow scars, “I promise I’m just unwell. I didn’t wander off on Winter’s Eve, it was just ill-luck, I tried to help someone and got turned around, I explained it all to Sister Diligence and she said she understood …”

“Yes, yes, I heard. I heard. Was it very frightening, Fidelity? The dark nights are frightening. I just want to know what might be troubling you.”

It had been frightening — calling and calling without an answer, not calling too loudly for fear of the dark and what it might conceal, leaving the drunk girl propped up, following the remaining torchlight down one hall or another, seeing a figure and feeling hope that they had come to find her and then realizing they were shambling and drunk, someone to slip back from, back into the shadows, which was how she’d ended up there in the long hallway with the tapestries, watching and afraid …

“Fidelity? The way your eyes go distant, daughter — tell me what you’re thinking about.”

That was what Temperance had said to her the prior afternoon, sitting in the refectory with Gravity and Grace, their chatter dying away without Fidelity quite realizing it – you’re so far away, Fidelity, what on earth are you thinking about -- and then when she tried to answer her friend the weight became a vise that squeezed her stomach, squeezed her throat, and then she was on her knees and everything was coming out of her at once.

“I’m just thinking about the funeral,” Fidelity said, in what she hoped was a plausible tone. “I was listening to the singing and thinking about the emperor. It’s so awful, thinking that he was — that he was falling to his death just as I was wandering in the dark. And I was frightened. I was. I’ve had bad dreams. And also, also Reverend Mother, I’ve been thinking about the princess. She was so kind, so kind when we visited with her, and now, now I’m just thinking about what the princess must be doing right now, how awful it must be for her …”

It was plausible because some of it was true — the dreams, the awful thoughts, the fear. She probably would be thinking about Alsbet, in a world where nothing strange had befallen her on Winter’s Eve. And in a sense she was still thinking about the princess — not imagining what Alsbet was doing with her grief, but what she might do with the knowledge that Fidelity now carried.

“Oh, grief and all, I suspect she’s still thinking about her handsome prince,” the Reverend Mother said lightly. “I’ve seen three emperors, daughter, and his soon-to-be-majesty will be the fourth. You’ve never seen any but Edmund, angels rest him, but heaven called him home and we mustn’t find anything fearful in that. You’ll feel better. You’ll feel better.”

She sounded all sincerity, indeed she probably was all sincerity. She could be especially watchful for the sake of her agreement with Lord Arellwen and also see herself as a mother to Fidelity — there was no contradiction there.

But Fidelity’s mother was dead, and all the kindness of the sisterhouse couldn’t help with her secret. The holy wouldn’t know what to do with it, the rest couldn’t be trusted with it. There was nowhere else to put the weight.

“Well, Sister Fidelity,” the Reverend Mother said, brushing her lightly on the forehead, just below her cowl, “I will pray for you tonight. And I expect you will be back in your cell this evening, and with us for the morning Orison tomorrow. Yes?”

She nodded, all agreement, anything to clear the older woman from the room. And when she was alone again, alone with the empty beds, she forced herself to get up and walk to the window, feeling the heaviness everywhere inside, heart and bowels and liver, her throat when she swallowed, her lungs when she exhaled.

There was a bird, a single cardinal, strutting on the gutter running just below the glass. It eyed her curiously, a dream or image come to life.

“Do you know who I am?” she whispered through the mottled glass. Somehow its gaze seemed to change from curious to knowing.

“Do you?” she said again. “Do you?”

She was Sister Fidelity, and yet she was not. Her name was Rowenna, and she was the daughter of Edferth and Ilbet, sister of Willa and Hilwen, from the township of Balenty in the earldom of Bluehaven.

She was Rowenna of Balenty.

She was Rowenna of Balenty, and she knew who had killed her emperor.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Falcon's Children to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.