The House of Birds

The Falcon's Children, Chapter 7

This is Chapter 7 of The Falcon’s Children, a fantasy novel being published serially on this Substack. For an explanation of the project, click here. For the table of contents, click here. For an archive of world building, click here.

The common room was quiet. A Ysani merchant smoked in a corner, nursing one of the larger jars of ale, awaiting an assignation or relaxing after one. Arella and Fal were playing cards with Alf, one of the bodyguards, the sweet-natured one who couldn’t grow a beard. The boy Frek was stirring at the fire, trying to coax a little more life from the embers before his next trip to the woodpile.

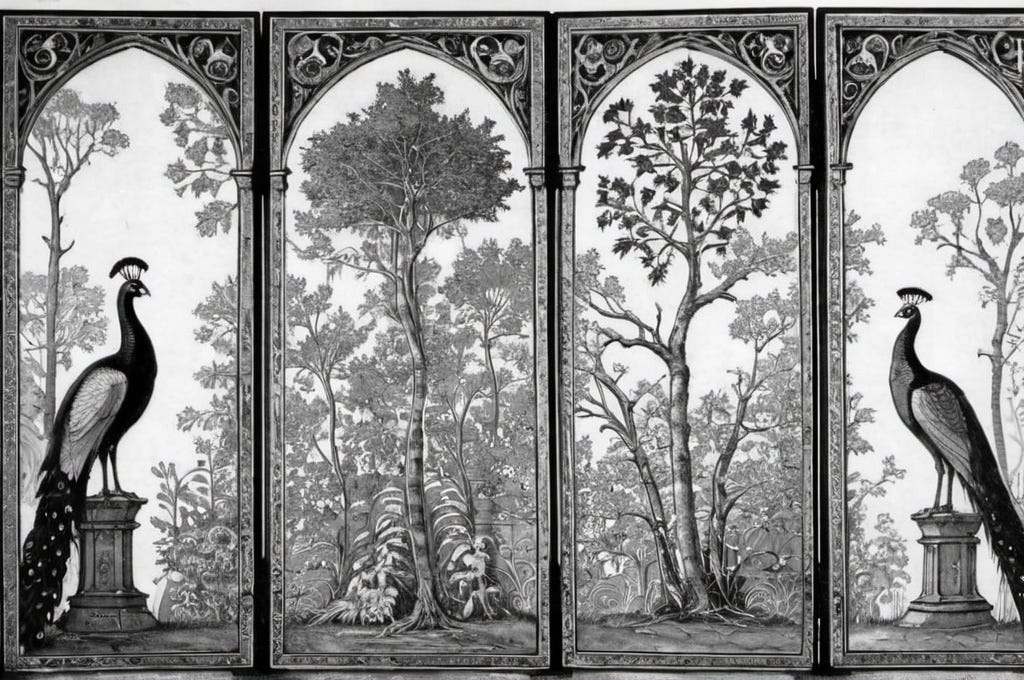

Shadows hid the birds and their colors, muting the peacocks and redwings, the goldfinches and bluebirds, even the phoenix near the musician’s stage. Rowenna was supposed to be cleaning the bar, scrubbing away the residues of the previous night’s servings, but no one was paying any particular attention to what she was doing, so she idled and dawdled at the work and tried to think.

You are not a prisoner here, she had been told at the start, after Reffio had carried her stupefied from the angel’s statue through Rendale’s dark, with two of his pidges, his urchins, his spies and messengers, nipping at his heels.

He had taken her to a bedroom, a bed softer than anything she’d known, and she had slept there like a dead person, all through the day and back down into the night again, waking for an hour to terror and mystification in the wee hours, somehow falling back asleep, and waking fully in the late morning of her second day in the House of Birds to a smiling, maternal face above a shelf of cleavage.

That was Arella, her first guide to the house — kind eyes, ringlets, a long horse face. She helped Rowenna into a simple dress that felt somehow at once light and cozy and led her to the kitchens for a reviving meal — the warmest porridge, the reddest apple, the sharpest cheese.

While she ate and after, the older woman kept up a steady stream of conversation that never once touched on where Rowenna had come from or how she had ended up in a bedroom in this place. Nor, for that matter, did Arella’s patter tell her anything specific about what kind of place this was, beyond one apologetic-sounding reference to “the clients” in a story about how a badger had accidentally found its way into the kitchen during the Winter’s Eve preparations several years before.

But by the time Arella was leading her up a stairwell and through a maze of corridors to meet the Lady, Rowenna understood well enough where she had awakened. It was a place like an inn, with endless doors, glimpses of bedchambers — but all the people she saw were women, all of them seemingly known to her companion, a few of them red-lipped and painted with strange colors or with bright feathers in their hair, a few in outfits that looked like what she imagined fine ladies wearing in the Castle, one masked like a white owl and one like a goldfinch, and everywhere more flesh, more neck and bosom and ankle and calf, than she had seen from any maid or matron in all her travels, all her life. From somewhere beneath them rose a sound of music, pipe and zither, that seemed too quick and loud for midday, and a spiced and perfumed flavor occupied her nostrils as soon as they reached the second floor.

Mostly the walls were bare or draped in deep autumnal reds, but each door bore a crude painting of a brightly-colored bird, and around one turning there was a real painting, a circular image ringed with gilt, in which two figures of women reclined while small angels fed them. It could have almost been an image of blesseds in the Bluehaven temple — except that here the women wore not a stitch, displaying scarlet nipples and exaggerated hips, and the angels feeding them were bearded and grinning and weighed down with more than fruit.

When folk in Balenty talked of cities they talked of many things, but there was always a special relish to the stories about bawdyhouses and brothels — stories that were generally just cautionary tales about girls who went astray, who wanted to escape their fathers or husbands or some such foolishness and ended up paying dearly for their folly.

Hilwen, when she aimed to shock or nettle, had sometimes said that the girls in a stories seemed no worse off than a country girl married against her will to some fat old widowed farmer, except that at least the bawdyhouse girls got a little money of their own out of the bargain.

But Rowenna believed in Balenty, Rowenna took the moralizing seriously, and short of being stabbed in an alleyway her fears of what could go wrong in a city had always included her father being ruined and her being forced to sell her body, a phrase that somehow evoked both sordid luxury and barnyard animals, silks and velvets and billy goats in heat.

Yet now that she had seen the worst, the alleyway knifing, her da’s body with its bloody smock, the second-worst held little terror for her. Whatever was happening in this house might might be sinful, it might be disgusting, it might be all drudgery and sorrow, but it wasn’t men with sharp blades hunting her through black streets under uncaring stars.

The thought that her new friend Arella might be a ruined woman was uncomfortable and strange, but it didn’t actively frighten her: There was simply too much distance between Arella’s bosoms or the naked women in the picture, which were merely embarrassing and strange, and a body in the alley and a deep-voiced shadow standing over Hilwen’s bed, which were raw sweating terror whenever her mind turned back to them.

No, whatever this place was, whatever it threatened or promised, the real fear lay outside its walls.

Those were the thoughts in her mind when Arella rapped twice at a studded black door, which opened to reveal a figure whose size and shape and features made Rowenna gasp and reflexively shrink back. He seemed unperturbed by her reaction: The bald head bent and the meaty hands opened to her, welcoming, and the voice came out just as strangely soft and light as she remembered from the city dark.

“We barely made an acquaintance the past night, my poor pretty lady,” he said to her. “My poor pretty girl. But I’m Reffio, I’m the humblest servant of the House of Birds and its noble lady, and I’m pleased to be your servant as well. I’m glad to see you your feet. Will you come along inside and meet the lady, and let us hear your story?

It was all too strange, and then the lady herself was even stranger — the milky eye, the high collar, the raptor’s face, the odd accent and emphases, the heavy table in the vast room with its couches and tables, its sculptures and bursts of flowers, the vast carpets with their wood ducks and wild geese.

Arella disappeared and Rowenna sat alone with the two of them looking at her from the far side of the table, the mistress and her man, like a child in a fairy tale confronting the giant and the witch together. And when they asked, she told them her story — because what other choice did she have?

But not all of it. She had a little slyness, more than she expected, and she didn’t see how telling these strangers all about the fox-faced man and his deep-voiced master would help her. Right now, knowing nothing about her, they seemed kind enough. (Kind enough for pimps and panderers, her Balenty voice interjected.) But if they knew that there was some mystery around her father, someone powerful in this city who wanted him dead and wanted his daughters for some purpose, their kindness might turn mercenary, they might be quick to go looking for the powerful someones and even quicker to sell her off to them.

She didn’t really know how big a city like Rendale felt for the people who lived there, but there seemed a decent-enough chance that a man like Reffio would know the fox-faced man. And if he knew the man, the chances seemed better than a coin-flip that he’d give her to him, if the price were right — and she had nothing to bargain with herself.

So she told the less intriguing version of her tale: The farm girl whose father tired of farming, the country folk hoping to make something of themselves in the imperial capital, her father going out at night for some business dealings and never coming back, and her awakening to find him missing and going out to look for him, going out through a door someone had left open and finding him dead in the dark outside the inn — at which point, well, she had simply panicked, because after all who wouldn’t panic at such a sight, and set off running wildly into the Rendale night. And she was grateful, so grateful, that they had found her and taken her in, and she hoped there was still coin back in their room at the Snow Goose with which she could pay for the food and hospitality, and probably she should find someone in authority and report her father’s murder … and at this her slyness and caution gave way and she let herself begin to cry.

Reffio was there with the handkerchief, his bulk somehow gliding to her side and then back quickly to his station, and while she blotted at her face she could see him exchanging glances with the Ladyhawk that spoke eloquently in a dialect she didn’t understand. Then the mistress of the brothel spoke:

“Thank you for the truth, child. I am not fond of liarrrrs, and I like to know what I’m dealing with. Reffio here is fond of brrrringing in his strays, he has a soft heart. But I always ask him to find out a bit more about them, and whilst you slept he was busy asking questions at the Snow Goose …”

“I knew where to go because saw you there that night,” he interjected, “looking like a lost little fawn in the deep woods …”

“… and I’m afraid the news from there is bad, child. Your da is dead, as you saw, and your room was rrrrrifled, and your sister simply vanished. Now, Reffio has his ways of finding things that get lost in this city, and if she’s out there living we can hope that she’ll be found. But you’re old enough to be told the truth: When there’s a murderrrr and afterward a lovely girl goes missing, the most likely place to look for her is at the bottom of Lake Orison.”

She was old enough. She had known it already. She would not think about it, she could not think about it, but the truth was that she had run and left Hilwen to her death.

“You understand? Good. Good girrrrl. So here’s where you stand now. Your father’s dead, and it’s not harrrrd to see what happened. He came here, found men he thought were his old frrrrriends, and set about boasting to them about how much money he could brrrrring to some investment. And these friends were wicked men, and saw no need to go into business with your father when they could simply follow him back to your inn and take what he had, with a knife in the dark and a quick trip upstairs. Mayhap they paid off someone in the inn to find his rrrrroom — if they did Reffio may be able to learn something of the business. Your father did not say where he was going, in which tavern he was meeting them? No? Well, still, he may be able to find something there as well. He is … rrrresourceful.”

“The little pigeons that found you find a lot of other things as well, little one,” the big man said, in tones that were distinctly pleased with themselves, and she wondered if those pigeons knew the fox-faced man …

“But for now, my girrrrrl, here is where you stand: You are homeless and penniless, in a strange city, far from family and from home. We are generous here, you may certainly stay another night, but this establishment is not a home for orrrrphans; for that you would need to apply at the Temple, and prrrrrobably the Gray Sisters would have a pallet for you within a night or two. There are good women there, some girrrls come out with a good chance in life. But I am only being honest when I say I would not choose it for myself.”

“Then what should I choose … mistress? What choice have I?”

She had to ask the question, even though the answer was already apparent.

The Ladyhawk cocked her head with a bird’s assessing manner. “You strike me as a clever girrrrl as well as a honest one, so you must already know what sort of house this is. You will have hearrrrrrd stories, I’m sure, where you came from, of places such as these. I will not say that they are all false, only that they are untrue of this establishment, this business. Here we help our girrrls: As they labor, so they are rewarded, in a ways that a poor woman without frrrriends or father could never be outside these walls. Some stay a long time, as long as beauty lasts; some tarry a little while, earn what they need, and go elsewhere — as you might go back to your village, if you liked, carrrying whatever story you preferrrrred along with the coin you make for me. But either way the work is no harder than many other kinds of work, more pleasant in some ways, certainly tiresome at times — but with Reffio here, Reffio and all his friends, it is always, always safe. And if you leave here, a girl alone like you, no coin, no man, you may come to the same work, but without the safety, without the warmth, without any comfort at all. And I say this to be honest: You may die.”

“The work,” Rowenna said. “The work is to lie with men.” She sounded a fool, but she had to say it.

“Depending on the man there might be more than just lying involved,” Reffio said with a burbling chuckle. The Ladyhawk snapped her finger angrily and he looked abashed.

“The work is to entertain men with the gifts of your body, yes. You may find some entertainment for yourself as well. Or you may just act as if you do. But either way you will be paid, in real coin, for something that girrrrls your age, girls in your little town no less than girls in this city, gladly do for pleasure.”

“Sinful pleasure.” Her voice was a whisper, and she wanted the words back.

“Yes indeed,” the older woman said sharply. “Sinful pleasure. This is a house of sin, a house full to the brim with sinners everrrrry night and day. But I promise you this, so is the fine Castle up the hill from us. So is the Temple when it’s crowded on the tenday or the feasts. So is any sisterhouse, the inn your father died outside, the small town where you were born. No man lives frrrrree from sin, that’s how the litany begins – and no woman either. My girls all make a confession on Atonement Day, like the Law bids. And do they have more to confess than all the rest in this city? No, I do not think so. And my dear girrrl, I know whereof I speak.”

She leaned back, framed in the chair’s leather. “So here is my offerrrr. I run a fairhouse, I’m a fair woman, and there’s no need for you to believe my prrrretty promises right now. You can see for yourself. No girl your age can begin without training. You’re blooded, yes? But a virgin, yes?” The questions were asked as though the answers were self-evident. “So you give us, say, four or five months. Till Winter’s Eve, let’s say. You work the common rrrroom, you wait on guests, you learn to talk to them, you learn to dress and walk … all things a girl should know no matter what destiny she has. In those months you have a soft bed, three meals, fine company, and prrrrotection, should you need it, from any … aftermath from your father’s tragedy. And maybe in that time, who knows, your sister is found, something else happens, you leave here happy, we’ll be very grateful to have known you. But if not, well, then we will see what we will see.”

“Do you know your letters?” Reffio said.

She allowed that did not.

“Well that is also something we can prrrromise,” the Ladyhawk said. “All my girls learn to rrread. I run a house for sharp girls, hard workers, girls who want a better future for themselves. You’ve hard a hard time of it, you’re a long way frrrrom home, and it’s not a bad chance I offer here.”

“Better than the Gray Sisters,” Reffio said wisely. “Better than the street.”

“And if you choose to stay with us,” the mistress of the House of Birds told her, her voice dropping to a gentle, soothing place, “if you say yes today, you should always know one thing about this house: You are not a prisoner here.”

In some ways it was true. Four of the year’s nine months had passed since that conversation, summer following spring and then autumn’s chill enveloping the city, and Rowenna knew that now, right now, she could give up cleaning, set down the cloth, climb the stairs to her bedroom, collect the handful of coins from where she kept them hidden in a small cloth inside the mattress, take the cloak that they had given her for the early snowfall, and walk out of the house, out through the public-facing tavern, out into the Dockside streets, and nobody would stop her.

She knew because she had done it many times, sometimes in the company of other girls but sometimes on her own. Not so often in those early days in the house, when her dreams were always of Hilwen and her father, when she expected to see the fox-faced man come through the doors of the common room every time she worked there, or else expected Reffio to summon her to some secret room belowstairs and hand her over to a faceless shadow. But with time she found that the sheer ordinariness of everyday life reasserted itself, even in a place as distant from her prior ideas of ordinary as the House of Birds, and the events of that one day and night receded deeper into her dreaming mind, leaving her waking self to expect the everyday instead — in the streets outside as well as the corridors within.

She did not go far, admittedly. Instead, whether in a group or in her solitary forays, she moved the way the other denizens of the house did, as a creature of the neighborhood, the docks and wharves, the inns and warehouses that flanked the crosshatched streets. She never retraced her steps from her dark night, never went up the Great Way toward the Castle or even as far as the Temple, never even considered making her way back to the Snow Goose. Instead she moved as though tethered to the brothel, her movements widening a little as the tendays passed but never leading her more than eight or ten turnings away from the Ladyhawk’s domain.

Within that limited space, it was known, they were all protected, they could safely walk without male company. No one in the waterfront would trifle with Reffio’s ladies, and if anything, when they moved around together they were often paid exaggerated gestures of respect.

This aura of protection could have felt imprisoning: After a little while she was known for her association with the House of Birds on almost every Dockside street, and some of the eyes on her might as well be the eyes of Reffio himself. But because it was the harbor, thronged all summer with riverboats and lake barges, she could also test the limits anytime she chose, by turning her steps to the nearest gangway and asking a captain or a mate about the price of passage back downriver — to Aldermark, to Felcester, to Bluehaven, anywhere at all.

The first time she did it she was terrified, but after a while it simply became a discipline, a way of proving to herself that she had a choice. And back at the brothel nobody ever said anything to her about this habit, no one took her aside, Reffio included, to ask why she occasionally made conversation with ships’ captains.

Which didn’t mean that his little pigeons didn’t see it, or that he and his mistress didn’t know. It just meant either that they were serious when they promised her liberty, or that they were serenely confident that she wouldn’t use what they had granted.

The Ysani trader crooked a finger at her, and she left her desultory cleaning and went to fill him another drink. She had seen him once before, she thought, early in the summer, which suggested that like much of the clientele he paid the House of Birds a visit whenever his travels took him to Rendale. He was probably her father’s age, with a red face and a thin beard sketched around his chin and cheeks. While she poured for him, he ran his hand up and down the table’s leg, up and down, up and down.

“How long till you’re ready, pretty girl?” His accent was thick enough that she wouldn’t have understood him in the spring; now she’d heard enough from every corner of the north to tell one Ysani from another, highlanders from lowlanders from moorfolk.

This one was a highlander, like Kittree, the blonde who slept next door to Rowenna and had a white scar across one cheek where an uncle had sliced at her, when I was just your age, the last atrocity in an orphaned girlhood full of them, one she’d left behind at sixteen to run away to Rendale.

“How long before you grow your wings, little bird, and fly?”

Rowenna smiled at the man and spun away, the way they’d taught at her. If you don’t feel like saying something, you can always just flirt with your hips. Not that her hips were all that much yet, but a little twitch as she turned away was still far better than saying something, because even thinking about answering his question filled her with a creeping disgust.

They said there was nothing disgusting about it, all her new friends, the kindly ladies of the House of Birds, the ones who told her to think of them as aunts and the ones who said she would be like a sister. They said they had no regrets: Kittree who had escaped her uncle’s blade and bruising fists, Fal who had been raised by the Gray Sisters and spoke of nothing but hard labor and misery in their house, Arella whose husband had gambled away all their money and died in a dockside brawl, Elfera who had worked the streets on her own, in terror and penury, until the Ladyhawk had taken her in. They all had stories of the world before, the world outside, that made the House of Birds out to be a haven, a place where the actual business was just a little thing, basically a costume party with some drinking and conversation and then a bit of simple fun, that kept them warm and safe and fed, and that gentled what elsewhere was just predation, cruelty and violence.

Then linked to this was a clear aspiration, the kind that the Ladyhawk had invoked in their first meeting — the idea that a girl who worked here who could hope for something else eventually, a hope that sometimes involved money saved, the money to claim the same independence as a man, and sometimes just the possibility of dependence on a single suitor, the client who fell in love or something like it, and took you away to be set up as his mistress, the mother of his children, even (there was one story, a treasured story) his lawful wife.

Such things could happen, the names and examples were known — Redera who ran her own wool shop up in Tribunal, Freya who was kept in an apartment near the Castle by a notable merchant, her son acknowledged by his father and training for the white priesthood, and then many other less-exalted cases. Yes, it was possible to begin in the House of Birds and have a happy ending, she believed it …

… but there was much else she recognized as well. You could save money but not so very easily, because unless you found a regular patron who slipped you coin in secret, much of what was paid was raked back for room and board, and the only way to stay ahead of that raking was to volunteer for extra duties, extra shifts, extra men, which even the women who made light of the act itself admitted was exhausting.

You could hope for a client who wanted to carry you off and make you his and his alone, but mostly what the girls spoke of were men who pretended to want that, who played games of jealousy and made vague promises of rescue, perhaps to salve their own consciences or perhaps for some sort of extra thrill in bed. And for all the happy stories there were others: The sicknesses that ran through the House and stayed with some of the women forever, the girls who died too young from disease or drink, the girls who became women and then old women without more than a few coins to their name, and ended, at best, in some menial job around the district when the clients didn’t want them anymore.

And the children — for though all her new friends assured her that there were ways to keep from bearing children, herbs and teas and tricks in the bedchamber, it still happened sometimes, and it was more likely to happen the more business you took on. Then there was just a brutal choice: To take the child and leave with whatever little money you had earned, or to give the child up, to the Gray Sisters or some other place for orphans, handing them the very life that you yourself had tried to escape.

Or to die in the birthing bed, of course — not a dying wife, a dead mother like her own, but just a dying whore.

So for all the determined cheerineess of many of the women, the shadows ran long in Rowenna’s thoughts. Especially because clearly not everyone was as cheerful as the friends who tried to make her welcome. There were women who mostly sulked or griped or fought, women who didn’t speak to her or to anyone save when it was required, and stranger cases like Korysa, whose story no one knew, save that she was clearly a savage from the north, a tribeswoman with snow-white skin and jet-black hair and wrist tattoos, who carried herself like an exiled princess (maybe she was) but bore in her proud face a look of everlasting misery and shame.

Then there was Val, the girl who had been her common-room companion for the first few tendays at the House. She was another of Reffio’s finds, her parents carried off by a winter fever leaving her in charge of three little sisters in a Winter’s Town shanty, and she had a clear and level-headed plan: Just a few years at the House, with all the money she earned going to keep a roof over her siblings’ heads, and then when they were all old enough to take on work she would quit and take an ordinary job herself, having done the necessary thing, and try to forget it ever happened.

Rowenna admired her clarity and certainty, her mix of grimness and good cheer. But just after Summer’s Door she was elevated, as Reffio called it, the word rolling around in his mouth like he was tasting it. This meant being given to one of the patrons who were known to to pay specially for a new girl, a virgin sacrifice; it meant the same kind of experience that waited for Rowenna, whenever her own apprenticeship ran out and the choice finally came around.

And after it happened, after her first night as a working member of the House, it wasn’t just that Val vanished from the common room; the person Rowenna had known vanished entirely, her personality seeming to fold up and stuff itself away into some deep recess in her soul. The cheer was gone, the conversation was gone, only stoicism remained. And when Rowenna finally found the courage to push against that surface, to ask her former companion about the night, the act, the change, the answer was a single curt sentence and a quick turning-away: Was what I expected, no use talking about it, and no use bitching neither.

These were things that Rowenna carried with her on her harborside excursions, the knowledge and the fears that sent her back, again and again, to the gangways of boats to ask about the cost of passage south. The prices were high but she had a little coin — coppers that were the residue of her wages after the money taken for her food and bed, supplemented by a few silver pieces left by patrons in the common room. (The latter money that was supposed to be given to the House, but there wasn’t always someone to watch when she was waiting on the men or cleaning up.) It was enough, at this point, to imagine buying a place on a riverboat — not a real room like the one her da had taken, but a place to sleep at least, all the way to Aldermark and Bluehaven if she wished.

But then — what then? She would be at the world’s mercy, much more so than right now. Coin to buy passage wouldn’t buy protection from the sailors, she knew that well enough, and if she reached Bluehaven unmolested she would be in the same place she found herself already in Rendale, but without even the dubious protection of the Ladyhawk. Perhaps, perhaps, she could simply walk the road from Bluehaven to Balenty, or find someone going that way who would offer protection — but just as likely she would end up robbed and raped and dead on the roadside as sure as her father ended up dead in that alleyway outside the Snow Goose. And if she made it to home, blessed home — well, she’d be there without a father or a family, without money, without anything except the remembered friendship of people who had probably forgotten her family the instant they disappeared.

She supposed she could throw themselves on their mercy, work as a hired girl, claw and fight to reclaim the simplest of dreams — her own house, a boy to marry, children who didn’t need to be given up to the Gray Sisters, a life as Rowenna of Balenty again. It could be worth it, it would be worth it if it worked — but the river and the roads were so long, her coins were so few, and then every time she imagined the world beyond these walls and the Dockside streets, the shape of the fox-faced man and his master were always there, shadows between her and the light.

The boy Frek had disappeared, out to get wood she assumed, but suddenly he was there at her elbow. He was the exception to the Ladyhawk’s rule: The sandy-haired son of one of the house’s women, his father possibly a Skalbarder by his features, who hadn’t simply been handed to the Gray Sisters and forgotten after he was born. But that was because his mother had died bearing him and there had been a promise to the dying woman — a hint of humanity, maybe, behind the cold gaze of the mistress of the house — that he would be fostered in the House of Birds, as a servant now and maybe someday as one of Reffio’s men.

He was about eight, tall for his age, with a big round face and bright blue eyes. “Rowenna,” he said, “there’s someone here for you.”

“What?” Her chest tightened, images flashing – the fox-faced man come for her at last, Hilwen somehow alive and ready to take them both back to Balenty …

“A priest,” he said, his child’s voice incredulous. “He’s out in the tavern. It’s a priest.”

The tightness gave way to a sinking feeling.

The priest, here. She was such a fool.

He was the only patron in the Hawk and Dove, sitting at a table with a tankard under the extremely suspicious eyes of the barman. Father Aldiff of the Abdielans, the Brown priests, a Ysani with a shock of black hair and a thick, bristling black beard.

She knew his name because everyone in the harbor district knew his name — because just over a year ago he had been placed in charge of the most run-down of Rendale’s shrines, its narrow belltower squeezed between two fat warehouses just a few streets away from the House of Birds.

The shrine was Mandoran-built and ancient, its stones gone brown with centuries of of filth and damp and lichen, and the statue of its blessed — a martyred Mandoran missioner, patron of drunkards and lost sailors — stared out across the teeming wharves with a mossy, crumbling gaze. An assignment there was something of a punishment, and rumor said that it was literally so in the case of the new priest: In his prior posting in his native Mabon, he had made a name for himself with scathing sermons about the immorality of the local nobles, and particularly the rumored whoring of Donff mac Carroad, the brother of Mabon’s duke. So it was assumed that this rather more arduous posting was his reward for causing political trouble for his order.

But he had made the most of it. The harbor district’s transient inhabitants weren’t know for their tithing — sailors were more superstitious than pious; merchants were neither — so there were no funds to repair the crumbling stone or replace the dying candles. But Father Aldiff brought a restless energy and a gift for vigorous sermons to the shrine, and soon it was drawing more than just the usual collection of temporary penitents to the tenday sacrifice. The black-bearded cleric became a popular presence in the district, striding about the streets and alleys, paying visits and calling out greetings in his cheerful, Ysani-accented voice.

Few people outside the Dockside precincts had heard his name, and presumably the priest-secretary responsible for his posting and the archpriest who approved it, comfortably ensconced in the priestly palace that abutted the temple, seldom thought of Father Aldiff of Mabon, toiling away in the seedier recesses of the city. But from the Long Wharf to the wool houses, from the White Dragon Inn on Foul Street north to Tavern Row, Aldiff was a household name.

Some of the house’s women went to the sacrifice — more went than before Father Aldiff had come to the shrine — and Rowenna often went with them, praying fervently but without much hope, listening absently to sermons that were usually about the transience of life, the folly of busying yourself in work and pleasure when Azriel might call your name tomorrow.

Then on Atonement Day they all went, just as the Ladyhawk had promised, all the House’s women and all its servants going out in raw gray weather to join the long lines of penitents snaking their way toward the grill where the priest sat hidden to hear their sins, and then to the altar beyond where they made obeisance and departed, shriven, to begin another year of sin.

In Balenty her confessions had been frivolous, a child’s list of petty failings. Here Rowenna shuffled forward in a kind of terror, reaching the front after an hour, kneeling and hearing herself say:

“I let my sister die. And I’m to be a whore. Mithriel forgive me, Raphiel shrive me, Azriel keep your hand from me, all of heaven hear my prayer.”

In Balenty no matter what she said, the priest just gave the penitent’s blessing. That was the rule, she thought — no matter what was confessed they blessed you and the line moved on.

But Father Aldiff, behind the screen, made a hissing sound. “How did your sister die, child?”

Should she answer? Behind her the line was long, with Arella and Kittree at the front, just a few spans away.

Her voice became a raw whisper. “She didn’t — I don’t know if she died. We came to Rendale with my da, from Balenty, near Bluehaven, in the country… he was murdered, I ran away, left my sister with the men who did it … I don’t know what became of her.”

“It’s not a sin to run away in fear. But what do you mean that you’re to become a whore? This is at the House of Birds?”

“They took me in.” Her voice was mouse-like and shrinking further. “They’ve been kind to me. But I don’t want — I have to choose — I think I’m going to become a woman there.”

“How old are you, child?”

She’d passed her name-day a month ago, barely thought of it. “Fourteen, father.”

“Fourteen. And that’s old enough to work at your … at the House of Birds?”

“It’s … I haven’t … but at Winter’s Eve, they say if I wish to stay that I will, I must work for …”

“I understand,” he said. “I understand. You are forgiven. You are forgiven. In the name of Mithriel, prince of the Archangels, and Raphiel the merciful, I declare you shriven. Go now to the altar, daughter of men, and pledge to sin no more.”

That had been three tendays ago, or thereabouts. She had worried that she had done something wrong or reckless that would come back to her or to the House, but then that worry receded into the background with her other fears.

But now he was here. A handsome man, that priest, Kedwen had said of him one tenday. if he ever falls I hope he falls with me. And it was true — a strong jaw beneath the beard, a high forehead, keen brown eyes.

“You’re Rowenna?” he said. “Come, will you sit with me?”

She sat with him, shooting a glance back at the barman, wondering how long it would take Reffio or the Ladyhawk to learn that the priest was in their house.

“We’re not supposed to see anyone through that screen,” he said, a wry note in his voice, his moorland accent. “But we see shapes, and I’ve seen you at the sacrifice, with the rest of the … ladies. So learning your name was easy enough. And I want to thank you: It’s a priest’s task to know all about his flock, and I’ve learned a great deal since your confession — about this House, and about its place in the city, about my superiors. About wickedness.”

“Please,” she said. “Please. I thought confession was a secret. I don’t want any trouble for the House, for the Lady … I mean, they’ve been good to me here, I wasn’t trying to make trouble.”

“Oh, it is a secret, don’t you fear. But if a man confesses a murder on Atonement Day I can for sure ask a few questions in the neighborhood about what bodies might have washed up recently. And if a girl tells me that she’s being made a whore against her will, well then for certain I can find out a little more about how that could happen in a city under the emperor’s justice.”

What had he done? “Against my – no, that’s now how it is, I’m free here, free to go, see I’m free talking with you now, Father …”

“Ah, I’m sure they’ve told you that, I don’t doubt they have their own sense of justice. All men do, the memory of heaven plays even on the wicked and the wretched. But you’re but a child, how could it be aught else than against your proper will? Just think on the words of the holy books. What the rich man calls freedom, the poor man calls his chains. You can be free and still in chains, Rowenna.”

She felt the truth of it, and murmured: “But I have nothing, Father. I have nowhere else to go.”

“There’s always another place to go,” he said. “Such wickedness … I went to the Temple, child, all the way to the archpriest’s secretary, as high as an ordinary priest can go, and told him that I had learned that under the law of virtue and the emperor’s justice there was, in this very city, a house that would prostitute a girl of fourteen. And he told me not to be so simple, so naïve — that men have their nature and need places to let the evil out, that girls can be seducers just as easily as grown women, and that anyway this House has powerful protectors and the Temple lets it be.”

He laughed. “He said it as if I were the naïve one! The things that I have seen and heard, compared to these cossetted darlings at the Temple — black murder and worse. But if we cannot try to save the innocent …”

His passion vibrated in the air, and for a moment she wanted to just say, take me away with you, not even knowing what that might mean.

“So I cannot bring the Temple to your aid, Rowenna,” he said more gently. “But there are other choices still. The Gray Sisters, you can go to them – it’s hard work there, aye, grim work sometimes, I knew them in Mabon, I know why you might be here instead of there. But at fourteen you need not be giving them your childhood, you’d be giving them a few years, a little time to learn some art with which you might make your way in this city without having to sell your very self … Their door is open, just fifteen streets away, I can take you there today if you but say the word.”

“I know,” she said. “I know, I’ve thought of it. I just don’t know …”

“Well wait and hear the other choice. You said you were from the country, from somewhere near Greenhaven …”

“Bluehaven.”

“Bluehaven, aye. You must have some people there. The boats go downriver all the time, all it takes is coin. If you tell me what you need for passage home, back to your village, your family, the shrine can pay your way. I can help pay your way.”

She had no people in Bluehaven, but she had thought of going to Felcester instead, in search of her aunt-by-marriage and her cousins. More coin would help with that — but it had been so many years since she’d seen any of them, and if Rendale seemed so vast and mysterious she knew that Felcester was even bigger, and she might lose herself there as easily, a fruitless search ending back where she was now.

“I have a little money, father,” she said. “I don’t know … it’s not the money, I mean, I thank you, I’m grateful that you would offer, but my mother is dead, my sister is gone, I really don’t know who would take me …”

“Sure enough, sure enough,” he said. “But there must be someone, someone who wouldn’t want this life for you, someone who would want a lovely girl to help tend their home, find a good young man to have you as his wife. You don’t know enough of the world to make the choice you’re making now. You must believe me, priests — real priests, we see all of it, all that’s good and bad, and the life this House offers you is a life you’ll regret. And once you’re inside, once you’ve given them your virtue — well, the angels will still love you, Rowenna, you’ll not be the worst sinner in this city. But you’ll be a victim of sinners, of the worst of sinners, for all your nights and days. Faith, you must see that, child. I see it. This is my territory, it’s my task to see it. And I’m here offering any help, any help that you need to choose a different path.”

She believed him. She felt his goodness, radiating like warmth in the chill corner of the tavern. Without being quite aware of it her small hand had gone out across the board toward his.

“Rowenna.”

Reffio’s soft voice. Reffio’s vast body, seeming to materialize in the half-light of the room. The rings, the scars, and this time a flicker of his original menace, his chilly knowingness.

“The keeper of our shrine is always welcome here,” the bald man said to Father Aldiff, with a slight bow that lowered him almost to a normal height. “But I’m afraid Rowenna needs to come back and finish the work she was given. The cleaning, you know, Rowenna. It must be done now. And a customer is asking for another drink.”

“She’s free, is she not?” The priest said sharply.

“Free? Of course she is free.” Reffio spoke as if he were baffled by the question. “But she works here, Father, for her room and board. And she has tasks to do, which she probably just forgot about when she was honored by your attention. Yes, Rowenna?” He clapped his hands and smiled. “Now off with you, quick, before the cook comes hunting for me instead of you!”

It was true what he said — she did work there, she had tasks, and she obeyed.

She murmured “I’m grateful for your prayers, Father,” curtsied, and left the two men to face each other across the tavern table — passing back through the doors between the tavern and the kitchen, back through the kitchen into the common room, back into the House of Birds.