The Prince and His Father

The Falcon's Children, Chapter 9

This is Chapter 9 of The Falcon’s Children, a fantasy novel being published serially on this Substack. For an explanation of the project, click here. For the table of contents, click here. For an archive of world building, click here.

Benfred wrote to Alsbet from Meringholt all that winter and into the spring, letter upon letter, as if making up for years of neglect with a flood of undesired attention.

The details differed but the theme was always the same — the rumors stirring in the empire, the peril of their position, the need for her father to leave Rendale and show himself, the need to make marriages (Benfred was not subtle on this point), a cascade of demands couched as useful information.

They say that the emperor might be going mad. Not many say it, of course, and the common folk still remember the wars and most of them still love him. But the nobles are another matter.

Edmund must show strength.

Jonthen Cathelstan and Eldred Gerdwell have ended their quarrel; there is talk of a marriage to seal their families.

There is much talk that Padrec is too slow to marry, that he has taken a doxy from the west.

In Argosa, the White Rose is scrawled in alleyways, and some folk were flogged for doing so. I suppose that we should be glad that they were flogged — but one wonders what the iron duchess thinks. Perhaps she dreams of her little nephew as a king and not a duke. I know I would.

Do you speak with your brother? Perhaps the two of you might come to Meringholt for the Stag Tourney …

Cathelstan, Verna, Rilias — I do not think that any other house is powerful enough to even consider for a match.

Alsbet brought the first two letters to her father, but with winter’s coming the cold and dark had settled once more into his soul, and their every conversation just made her sense of prisoned helplessness increase.

He was not even especially drunk, he did not even say no to her importunings — he claimed he would consider a pilgrimage somewhere in the summertime, he said he was thinking on a marriage, in a year the time might be ripe, a betrothal at seventeen and a marriage at eighteen, he might write to Benfred himself to offer reassurances.

But she could tell that as soon as she left his presence, everything she deemed urgent was rolled into a heavy blanket and shoved into a darkened corner of his mind.

Her next stratagem, suggested by Gavian, was to take one of the letters to Orfenn Rell, the Lord of the Secretariat and her father’s spymaster.

This was no more effective. “We get many such messages, you know,” he told her sadly, “all rumor, no substance. Thank your uncle, of course — but tell him that it’s often useless to be told of rumors. We deal in facts — otherwise we would drown in suspicion.”

“Is my father’s throne in danger?” she asked him then, flat out, and Lord Rell sighed.

“The throne is always in some danger, Highness. I’ve run the Secretariat for nine years, and not one goes by without the rumor of some rebellion or plot – especially now that we rule the Brethon lands. It’s true that your father’s … his grief is making things difficult. But he is still the emperor, he still has the favor of the people, the favor of the legions, and we labor every day in this castle to balance out interests so as not to alienate the nobles. His being too — too long in mourning is not enough to make them rise. So try not to worry, I beg you.”

“What would be enough, my lord?”

“To turn rumor and grumbling into plotting and revolt?” The Lord of the Secretariat shrugged. He came from the Darkfens, where Alsbet had been once as a girl, on what must have been a visit to Sheppholm, but which came back to her as a strange memory of brackish water and cat-tails large as trees. “We can only look at history — at past rebellions — for a guide. I would say that as long as the emperor does not stoop into tyranny … arbitrary executions, futile wars … then the throne will be safe.”

“Safe even, as my uncle says, if my father seems to vanish into his grief? If he is absent from the realm he rules?”

“Absent — well, princess, you must remember that most of your subjects do not live in the Castle, or in Rendale. To them the emperor is always absent — just a distant presence, far above their local lord. Not so different from the archangels, in a way. A name they hear in the prayers at the tenday sacrifice, no more. So an emperor who grows … who grows withdrawn, as your father has sometimes been of late, is no different to most of his subjects than an emperor who makes a constant round of ducal feasts and tourneys.”

“Such an absent emperor is different to his dukes, surely. And they are the men that my uncle bids me fear.”

“Yes, but we have the legions, remember. That’s why they exist — to safeguard the realm, and so no nobleman even thinks of revolt. And I can tell you, sincerely, I see no sign than any duke is preparing to challenge the legions. So again — I pray, princess, do not let these troubles cloud your mind.”

That was useless counsel, so finally she made her way to her brother, contriving to separate him briefly from his Brethon friends, not showing him the letters but trying to summarize their uncle’s view of the situation, to explain his fears and warnings and hint gently at her own.

There was a certain relief in being even somewhat honest with Padrec, but her brother was no more helpful than Lord Rell.

“Benfred, these dukes … sister, why should we live in fear of old men?” he asked her. “Our father does not fight, but I do. The legions know me, our greatest general knows me, the young men of our empire know me. My friends and their swords are worth as much as Jonthen Cathelstan or Gerdwell or any Verna, any duchess.”

She said something about their uncle being better acquainted with the condition of the wider empire, about Rendale’s isolation — “and you yourself have been across the mountains for all these years,” she added, an observation that seemed to sting him:

“Yes, yes, I’ve been over the mountains and I’ve won for us the very thing that you say our uncle and our father both agree we lack — a great base of power, greater by far than any of our dukes’ cities, where the House of Montair can rule by right for as long as our line lasts. And yet instead of fully claiming it I’ve been summoned back, penned up in this Castle, given no real duties … listen, sister, I mean this sincerely, you should write to Benfred and tell him that he should speak to our father, to the council, and make the case that I should be crowned in Allasyr. That’s the answer to his fears — seal our conquest, seal our claim on Brethony … on Allasyr … and let the old dukes spin their webs as they like.”

“And as for betrothals, as for making marriages,” he went on, “why rush impatiently ahead of ourselves? There’s time enough for both of us. There’s no need to let an old man’s fears thrust us unready to the holy altar. Or even to make the choice for us at all — if father has grown weak before his time, why shouldn’t I find you a husband?”

His smile at this notion was meant to be charming, confident. “A husband as young and handsome as you deserve. Because, listen — my reign will be a time for youth, Alsbet, on both sides of the mountains, in Brethony and Narsil. And whatever darkness you’ve felt since our mother passed, you aren’t doomed to some choice between happiness and duty, certainly not yet. No, we can’t let the old men take what rightfully belongs to us …”

It was close to things she wanted to believe, but he kept talking and talking, his eyes looking past her, and after she left him all she could think was that he had only been talking to himself.

Meanwhile in the Castle life continued in the pattern of administration and entertainment that Alsbet had become accustomed to, for all that it had been her castle for little more than two years. Winter froze the earth hard and buried it in white; spring melted the ice off the lakes and flooded the city streets with mountain runoff; with the promise of summer her father suggested vaguely that she repair to High House for a respite — an idea that seemed absurd, impossible, like a voyage to the moon.

Instead she went more and more to the castle’s chapel – alone, not just for evening prayers and feastday sacrifices, to pray before the statues of the Archangels, the altars of the blessed, the images of sacred stories. Her mother had raised her children to religious duty without much religious feeling, an arid sentiment that was mostly confirmed by the white priests who served the imperial chapels, with their dry-as-dust recitations from the Histories and the Law, their sermons on hierarchy and order and the obedience owed to parents and to rulers, all the values associated with the Prince of the Archangels, their patron Mithriel.

But after her mother’s burial Alsbet had followed the evening litanies with the Blue Sisters, and somehow the female voices and the shadow of the order’s patron Jophiel — who was sexless like all the angels but more likely to be portrayed, and to appear to common folk, in a woman’s dress — made the prayers feel like more than just rote ceremony. It wasn’t that she was sure they were being heard, but it felt like they might be — and as alone as she felt in her father’s castle, that might be was enough.

That spring, she even asked some of the Jophielan sisters to join the regular evening meals that she hosted for the ladies of the court. It was not that strange a request; there were noblewomen who surrounded themselves with sisters (or, at slightly more risk of scandal, with priests), and many of the Jophielans were themselves daughters of noble families, even if their birth names had given way to religious ones: Marelwa mac Carroad becoming Sister Benevolence; Elspeth of House Farrow becoming Sister Clemence; a cousin of the Gedmens who ruled in Bluehaven becoming Reverend Mother Concord.

Still the Jophielans, with their veils and tonsures, were more otherwordly than the sisters who usually ended up close to duchesses and countesses — not cloistered like the White Sisters or unapproachable like the Blacks, but more set apart than the Reds with their medicines, say, the Greens with their plantations.

But then her own little court was not especially worldly either. Real courts, she knew, brought together women who were genuinely politically significant, either drawing them in with the promise of influence and importance, or else pulling them in as effective hostages. Not so in Rendale, the cold capital of a far-flung empire. Her step-grandmother Allara had made some attempts to draw Argosan ladies to High House in the summers but her mother, as a foreigner, had never tried to exert that kind of pull. And the Montairs had managed to rule effectively without taking noble hostages. We have gold and the legions, we don’t need pretty prisoners, her father had said once, as a younger and a prouder man.

So what she had instead was an awkward mixture of minor noblewomen, a circle divided between the young unmarried husband-hunting ladies-in-waiting, Lady Ellera and Lady Bella and Lady Freda and Lady Wildegera, and then the Castle’s older wives: Lady Wentwain, the stern spouse of the Lord Captain of the Falconguard; Lady Gaddel, the perpetually damp-eyed wife of the Lord of the City; Lady Titaria, the wife of the Lord of the Exchequer, whose scandalous past was sadly not something to be openly discussed at dinner.

Mostly thanks to Titaria it was not an altogether uninteresting group, but it did not fit together neatly, Alsbet herself was a weak center for the conversation, and any given evening tended to veer between pleasant gossip, stilted conversation and awkward silences, with little that was either heartfelt or artful in the style she knew that courts were supposed to cultivate.

Sadly the Jophielan sisters did not improve the interplay. They came in different groups, though always with the Reverend Mother. The ones who seemed most poised and confident were the ones who had exchanged titles for the veil, and they were the ones that the ladies of her court, the older ones especially, seemed most comfortable having at their table. But they were clearly there out of duty not desire, and their conversation was limited to pious platitudes — while the ones who seemed to actually appreciate the evenings were the sisters who plainly came from ordinary stock, either plucked from farms or shops for their singing talent and else youngest daughters given to the order for a price cheaper than what it would have cost to dowry them.

A few were aspirants, sisters-in-training, veiled but with their hair cut short and wrapped instead of tonsured, and she could feel them gawking through a thin mesh that did not entirely hide their features, or peeking around boldly when they lifted the veil for a sip or nibble at the plates.

One night there were two sister-aspirants there, Temperance and Fidelity the Reverend Mother called them, clearly friends by the way they moved together, and after the second wine course went around they giggled at something Lady Titaria said and couldn’t stop, shaking in their light-blue habits while her younger ladies-in-waiting laughed with them and the older noblewomen looked askance and the three full sisters sat stiffly, their judgment rolling through their veils in waves.

The young aspirants weren’t there the next time, and that next time was the last: The Reverend Mother offered deep apologies but the evenings were simply more of a distraction from their religious duties than she had imagined, the princess surely understood, they would be praying for her daily, etc. etc.

A few tendays later Alsbet saw the two of them, Fidelity and Temperance, leaving the Castle’s chapel late one evening. She had Freda with her, they were coming back from a small dinner with Lord Arellwen and the Janaean ambassador, and the not-yet-sisters dropped a deep curtsy as they passed. She paused and smiled at them and asked them to rise, and then asked if they remembered Lady Freda of House Weary, and when they had curtsied to Freda in turn she asked them what kept them in the chapel so long after the litanies were done.

The girls exchanged a glance, and Temperance said something softly about being assigned to lay out robes for the sisters singing in the morning, in a tone that made it plain that the task was not exactly an honor.

“Can I offer a man to walk you back to the sisterhouse?” the princess said, wondering if they were still being punished for their giggles.

No, they said, still murmuring, there was a guard at the postern door who watched them cross from the Castle to the sisterhouse, it was safe as anything, not to worry.

Then Alsbet told them she was so very sorry that they had not been allowed to come to her dinners again, and she hoped their Reverend Mother knew that anyone in the sisterhouse had an open invitation.

At this they both looked at her as directly as the veils allowed. “Oh highness,” Temperance said, her voice now breathy and not-particularly pious-sounding, “we had such a wonderful time, you were so kind. We’re the ones who should be sorry — for being rude and clumsy, I’d never met such great ladies, and the Reverend Mother, she felt …”

She trailed off with a glance at Fidelity who was obviously blushing — there was pink showing down her neck, just below where the wrap ended. But she gamely picked up from her friend: “She felt that we had better attend more to our pieties, Highness. But I hope one day we may come again.”

“Maybe there will be a different Reverend Mother someday,” said Freda, a notable giggler herself, and the pink on Fidelity’s neck became outright scarlet.

“Lady Freda, for shame,” Alsbet said easily. “The Reverend Mother will always respond to an imperial command, and perhaps I shall issue one someday — but only after you both are sisters in full, and above reproach in every way.”

“Oh yes indeed, highness,” Temperance said. “But we must be going — we will remember you in night prayers tonight, we always do.”

“And I will remember your sisterhouse in my own,” Alsbet said, letting them go off in a rustle of long robes, seeing them glance back for a moment, while Freda said something about being so grateful not to be prisoned in a house with only women under some old prig’s cold authority.

The two young women bent around a corner, blue against the dark.

“There’s more than one way to be prisoned,” the princess said softly, but her lady-in-waiting didn’t hear.

Later, in the languid high-summer heat, Benfred wrote again, with reports that Aengiss has been making a journey through the Heart. He visited me briefly, after Felcester and Cranholt and Bluehaven — on his way to a rare visit home, he said. He had much to say about what is happening in our Brethon lands, not all of it good. Still it is strange that he is traveling now, if things are becoming more unsettled.

Stranger still if he does not come to Rendale.

I’m sure that your Lord Rell already knows this, though.

And then this – I have been writing to Padrec. Thrice now, but still he does not respond. Can you speak with him? Can you ask him to reply to my letters?

Alsbet wrote back, and said that she would. But Padrec was gone by that time, gone to visit other friends in the Heart, and in Ysan, and his strange retinue was gone with him.

They returned as the hot summer days began to cool a little, and as more rumors came to the city of strange events in the Brethon lands — similar to rumors that had been shared in taverns since the conquest, except that this autumn they were more specific, the vague tales of “cults” and “rituals” given more substance than before.

It seemed that older ways were returning to Allasyr and Capaelya in force — not the gentle heathenism of the sun-god, Bronh, but the ancient worship of the spirits that lived, it was said, beneath the hills or in the mists that filled the valleys or somewhere deep in the trackless forest of the Mar Tyogg. The Aefae, they were called, the fair or kindly ones, and they had been propitiated in secret by country folk for as long as human memory and history recalled — with bonfires when the seasons turned, and animal sacrifices in times of trouble, and other minor rites observed more out of habit than conviction.

Under the empire’s rule, however, conviction had risen again. Roving prophets promised that these fairy spirits would drive the Narsils from the land and restore Brethony to glory. Rituals, replete with bonfires and sacrifices and chanting in Old Brethon, sprang up around the mounds that were believed to be gateways to the hidden country. Bands of armed youths roamed the countryside, waylaying travelers and even, on occasion, attacking legionnaires. There were cases of arson and vandalism in all the major cities, and incidents in which small hamlets were torched before any soldiers could arrive.

When a party of these Aefae worshipers were captured and brought to Tessaer al’Yrgha to face trial and execution, they somehow managed to put their hands on weapons while imprisoned and proceeded to commit suicide in bloody fashion in the Square of Dyr’ghaela, with thousands of people gawking. Their leader, a slender former priest of Bronh, managed the finest touch, killing himself by self-immolation.

As he vanished in a wreath of flames, he cried out that this was the same end that the true king of Brethony, the King of Hills and Trees and Water, had prepared for every Narsil.

It was shortly after news of this strange death came to Rendale that Edmund the emperor awakened from a wine-darkened afternoon’s sleep and realized that today was the day he had decided to speak with his firstborn son.

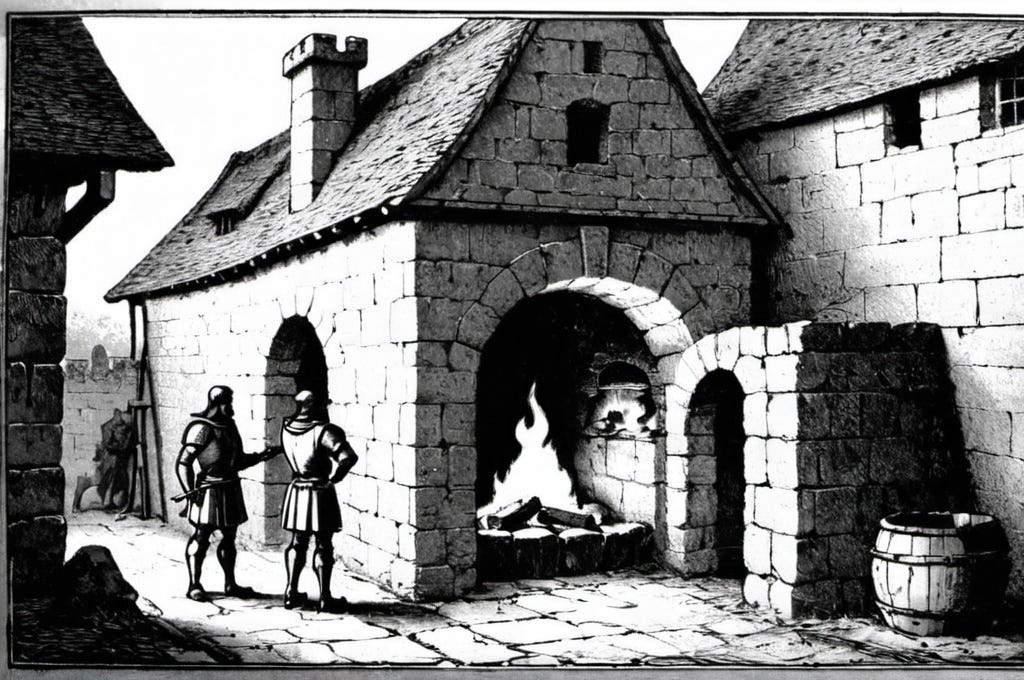

He found Padrec in the armory, watching the sparks fly as one of the smiths hammered away at a glowing piece of steel. The prince was slightly taller than Edmund, now, his shoulders broad and muscled, with a faint dusting of yellow stubble on his lean and handsome face. In the late-summer evening, the flickering shadows of the smithy flailed at his face and body and flung themselves behind him like a wind-caught cloak.

He made as if to bow when he saw his father, but the emperor clasped his son’s arm and gestured toward the darkening out-of-doors. “I need to speak with you.”

They had spoken often enough in the months since Padrec’s return, but somehow it had always been under the eyes of witnesses, as though they were both uncertain how to be with one another, and sought the protections of formality for discussions that might otherwise turn dangerous.

Now the prince seemed to tense at the prospect of something more intimate. “Can we talk here? I should like — We should like to see this sword forged, Father.”

“We?”

There was a clatter from another part of the forge, and a young man with a mass of dark curls framing a face that was almost feminine in its beauty crossed to the emperor and dropped to a knee. “Majesty,” he said respectfully.

“Maybe it would be better if we were to talk later, Father. Paulus and I are seeing this sword finished, and then we are going down to the river taverns for the evening. We can talk tomorrow …”

Paulus ...? He should know this young nobleman's name, Edmund reflected, but his memory had been slipping, and the minor families of the empire were so numerous, and there was a grinding headache gathering somewhere just behind his eyes. An Argosan name, so Paulus bar . . .

“Rise, my lord,” the emperor commanded with a distracted wave.

"Paulus bar Merula, at your service, Majesty,” he said, and uncoiled with a dancer's grace to stand erect. His eyes were dark pools.

“Merula, of course,” Edmund agreed, as if the name had been on the tip of his tongue all along. “Of … Kander-on-Tarcia – I knew your father, my lord.”

“A good man,” the lovely young lordling said softly. “Archangels rest his soul.” He paused, then turned his gaze on the Prince. “Padrec — if your father needs to speak with you now, then perhaps you should —”

“We are seeing this weapon done, Paulus,” the prince said.

His grating tone snapped Edmund’s mind away from the graceful beauty of the young earl of Kander-on-Tarcia. “There will be other blades,” the emperor informed his son, “and the taverns on the lake will still be open in an hour. I need to speak with you now.”

While I am sober, he might have added, but Edmund did not precisely admit such things to himself.

Outside, a group of younglings were thumping one another with wooden swords while the serjeant snarled and called down imprecations. The wind was sharper, a chill foretaste of summer’s end, and father and son moved in unspoken agreement to the shelter of the battlement that loomed over the west end of the practice yard.

“You are leaving in a week,” Edmund said, only half a question. “For the west.”

“For Tessaer, yes.” It was the agreement his council had made, to suit the unsettled settlement through which the empire ruled its Brethon lands: The year he’d just spent in Rendale was to be followed by four months in the capital of Allasyr, the prince’s not-quite-kingdom, where he would rejoin Alaben and Aengiss and the collection of Brethon lords and not-quite-rule. To be followed by another return to Rendale, and so onward in a cycle of travel west and east.

“I spoke with Arellwen yesterday.” It was yesterday, he was almost sure of that. “He told me about the conversations you have had with the council — about matters in the west, about the cults.”

“They have their plans laid, yes.” Padrec’s view of those plans was not disguised.

“Grain shipments from the Heart, a truce with the more malleable of the rebels … you object to these ideas?”

“I don’t object, father. But you know my mind on what Brethony needs.”

It was odd the way his son said Brethony — he gave it an accent, faint but clear, and spoke as though it were a real place, more real than the defunct Brethon kingdoms or even his own empire.

“And you know my will,” Edmund said, straining a little for authority. “It might be well for Allasyr if you were crowned, but it might not — you would still just be a usurper to most of these, these fairy-worshipers. And for now it would be worse for the rest of our empire, which must be ruled as well.”

The prince gave a shrug. “Your will be done, father. But you haven’t been there. The war is unfinished so long as it seems that we are aliens there.”

“We were aliens in Ysan, aliens in Erona, aliens in Argosa. We didn’t pretend that we weren’t conquerors. All these things take time. You must be patient. You’ll be emperor, and if you wish to wear two crowns you can. But you must see why the council is doubtful.”

“I see why,” Padrec said. “But I wish that they could see what I have seen. I wish they would listen to my friends.”

“To those Brethon bravos you brought back?” Edmund laughed. “They are fine young fighters, I don’t doubt it, and the girl is a beauty. But of course they want you crowned. Of course they tell you that being a king will set their land to rights. I had friends like those, once. Lord Arellwen was one of them — in your grandfather’s time. But young men are always overeager, and when they befriend a prince, well …”

“I’m not a fool, father. But they still know things that seven men sitting in a cold room in this castle do not. And Brethony is different than our other conquests. Older, prouder … it has a different god, a different tongue, a mountain range between us …” The prince has fumbling, but there was feeling in his voice. “If you had spent more time there, if you had come west when we last rode to war …”

“I fought there for four years,” the emperor said coldly. “I have the scars and aches to prove it. And this was not what we needed to discuss. There will be time to revisit the settlement after your return, after we see what comes of the council’s plan. For now we must speak of matters closer to the heart of our empire.”

He paused. Padrec said nothing. The clock-clock of the wooden practice swords seemed unnaturally loud.

“I know I’ve let certain matters slip in recent months. Matters that a ruler cannot allow to slip. Matters having to do with your sister, to begin with.”

His son rubbed a finger across the stone beside them, and a faint waterfall of gray dust went down the wall. “She seems well to me. Growing up and filling mother’s place here.”

The emperor blinked, and for a moment his gaze shifted and he felt himself staring through his son, through the squires and the serjeant and the walls of his castle, all the way to — where? To the Guardian peaks, perhaps, wrapped in forests and shadows, and a meadow above a shuttered High House where leaves had already begun to fall.

“Yes, her mother’s place,” he said at last, his mind returning. His headache was worse, and his eyes stung. “Yes. You’re quite right. She is growing up. And that’s the point.”

“The point.”

“The point being, that much as we might like her to remain as mistress of Castle Rendale, that will be the task of your wife.” He smiled, too weakly. “Which is the other point.”

“Again, the point.”

“Yes, again. So the point — both points — is marriage. It is time for these things to be arranged.”

“Why? Are the dukes demanding it?”

“Well — yes, in part. Before your return but also since: Cethberd Gyldenfold was here for the midsummer tourney, and I had to listen to him list all the reasons for a marriage alliance between our house and his. And I have listened to the same speech many times over the last two years. Every duke in the realm wants her for a daughter … or for a wife, if you count Eldred Gerdwell. I’m half-expecting the dukes we made in Allasyr and Capaelya to come pay her court soon.”

The prince glanced at the battling young men and grunted noncommittally. “Well, let them pay her court, and then let them dangle. Let them be impatient. She is only sixteen now. Let them wait for her.”

“She is seventeen now, and her mother was seventeen when we were married. And then – well, you are twenty-two, Padrec.”

“Meaning?”

“Meaning that we must betrothe you as well, and soon. The empire needs a certain succession. You need a match, and an heir.”

Now he could read a strong emotion on his son’s face, though whether it was anger or fear or some sort of desire was hard to tell. And the prince’s words when they came out were tight, any feeling condensed away.

“Am I to have any say in the match, Father?”

“I didn’t when I wed your mother,” Edmund said, trying for a hint of amusement. “But that doesn’t mean that you cannot. Still, I will be setting Arellwen to the task of considering it, and when you return from the west, if you wish, we might contrive to have you meet some of the candidates. Though in contexts that do not seem too much like courting … lest we give offense …”

“And will — will any of these candidates be Brethon?”

The emperor thought of the western girl who had come back with his son, the long legs and hair and the smile and the eyes that watched everything so intently. Was this what Padrec wanted? What he imagined that he wanted? A crown in Tessaer and some beauty from a minor beyond-the-mountains house as his queen?

“No, I don’t think so.” Edmund tried to make his tone gentle. “Especially not if you really intend to wear their crown. You are already half their blood. Your own heir could marry an important Capaelyan noblewoman, perhaps, should the times demand it. But for now we must bind ourselves more tightly to our lands and subjects here …”

Still the flat affect. “Well, then, father, I suppose that you and the council should simply choose for me. You can even have her waiting, all dressed and pretty, when I return in the spring. I’m sure you’ll be good at dressing her up.”

“I’m sure ... What does that mean, now?”

“Nothing, father. Just what I said. I said you should find me someone, if it must be done, so that I can have an heir ... and I think you should wait a little longer with my sister. Don’t keep her shut up in this drafty castle, either. Send her out — let her meet some young noblemen or some . . .”

“Let her meet — no, Padrec, the whole point is that she is young and at an age for romance, which can be a dangerous thing. Your uncle Benfred, you must remember his sad tale. I don’t want her being swept off her feet by anyone unsuitable — not when she is required to marry for the good of the empire. Like you, Padrec. And of course, it would be better if someone wasn’t just waiting for you … if you understood the reasons behind the choice, because you will someday be the one making our choices, for our empire and our house.”

There was a long silence. The sun had disappeared behind them, and the shadows covered the entire practice yard. The young men were collecting their equipment in the gathering darkness, and a flock of mountain geese appeared overhead in a southward-beating arrowhead of feathers.

“So this is how it will be, father?” the prince said at length, his voice no longer flat but bitter, his eyes on the ground. “You will become a spider in your old age, sitting at the center of some web, marrying your daughter off to some suitable duke and telling yourself that you are accomplishing something?”

“What the hell,” Edmund ground out after a barely perceptible pause, “is that supposed to mean? Do you think that such things as the marriage of his own children are somehow beneath the notice of an emperor? If so, you know exactly nothing.”

“I know that you sent away my brother, sent him southward, on some scheme that I do not understand, and now he seems lost to us, I’m told he barely answers Alsbet’s letters …”

“The scheme was for his health,” the emperor said softly.

“… and now you plot my marriage after I have been away for years on the business of the empire, winning battles and trying to learn to rule, and you behave as though I am still the child that I was when I left here. As though you have perfect wisdom, when you haven’t left Rendale in … well, how long has it been? Not just to ride to war — when did you last ride south into the realm? The real realm, not just this mountain fastness?”

Edmund’s eyeballs were warm coals in their sockets, and someone was rolling barrels through his skull. He needed a drink — craved it — and yet here he was, cold sober, trying to talk good sense to his own son, and what was his reward? This ...this contempt?

He tried to keep his voice soft, authoritative, edged with danger. “It sounds like you have a large complaint to offer about my rule, my son. By all means continue.”

“I don’t want to . . .”

“You have certainly begun.”

“I mean, that you wouldn’t listen . . .”

“I’m listening, Padrec.”

“You’re not —”

“What do you want to say, boy?”

“I want to say – to say that you can tell yourself that petty diplomacy, using your children instead of your weapons, is what a ruler does — you can tell yourself that, father, but it doesn’t change the fact . . .”

“What fact?”

“The fact that you haven’t really been trying to rule since you gave up fighting.”

“Gave it up? Is this something your friends say …”

“Yes, gave it up!” Padrec cried. “Yes! You left it to others. You left it to me, to Aengiss, to all those men who died in lands that now you just read about in dispatches …”

“Is it Aengiss who says this?”

“It is not Aengiss, father,” the prince said furiously. “It is what I hear when I leave this place, what I heard in the Heart and everywhere this summer. People say that the emperor does not wish to rule any more, that he shuts himself away, they say …”

“They say all that, do they?”

“They say it and in the name of all the angels father I have been here for almost a year and it is true. It is true. I do not go to many council meetings but you are not there. I hate the banquets but when I go, when my sister demands that I go, you are almost never there. All the council lords won’t say it, Alsbet tries to say it in this awful painful way, but you are lost, father. You are lost, and you have been lost ever since you acted — since you acted — since you acted like a coward …”

“How dare you!” The Emperor of All Narsil was suddenly, shockingly, screaming, heedless of whatever eyes and ears might be watching and listening, hovering in doorways and on the battlements above. “What in all the hells is the matter with you? I called you here to discuss the future of your crown —”

“No, you didn’t, father! You didn’t call me anywhere -- you came to find me. And where was I when you came? I was somewhere you haven’t set foot in years, somewhere with weapons and armor and maybe, maybe, just maybe, a hint of war and battle and courage and manhood about it.”

“You dare to —”

“Have you even held a sword since Naesen’yr, father? Have you? I think that an emperor should fight for his empire, not just scheme for it. Where were you in Allasyr, father, when I fought -- when you used me and Aengiss to do your dirty work for you?”

“I am your father ...you will not speak so . . .”

“Then why did you run away when it was time to fight? I bled for you, while you galloped off to the mountains and High House ...”

Edmund’s hands, the veins standing out purple, snaked out and seized his son’s cloak. He yanked Padrec to him and almost spat into his face:

“I was with your mother, boy.”

A flight of crows swept past the yard, cawing fiercely. The emperor’s head throbbed, and tears stood out in his reddened eyes. Padrec drew a sudden, ragged breath, as if aware that he had gone too far — but then his face hardened, and he wrinkled his nose, ever so slightly, as if he smelled a faint odor of bad ale.

“With mother, were you? Are you sure? Are you sure you weren’t at the bottom of a wine barrel?”

He hissed the last words, and Edmund cried out, releasing his son and stumbling backward, his fists balled and his head bowed. Padrec stared at him for a moment, and then turned and stalked toward the armory door, the flames and the waiting shape of Paulus bar Merula.

Outside the emperor crouched low to the ground, murmuring and fumbling at his belt. The yard was empty by the time his questing fingers found the wineskin.

It was, mercifully, still full.