This is the latest installment of The Falcon’s Children, a fantasy novel being published serially on this Substack. For an explanation of the project, click here. For the table of contents, click here. For an archive of world building, click here.

I have left this chapter outside the paywall because it’s an interlude, the paywall will reappear with next week’s chapter, you can subscribe here.

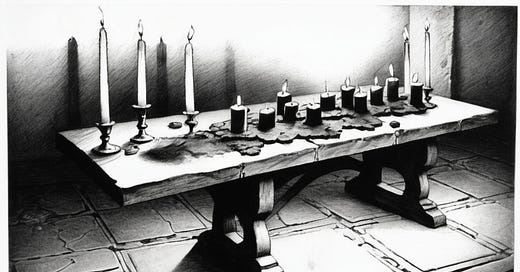

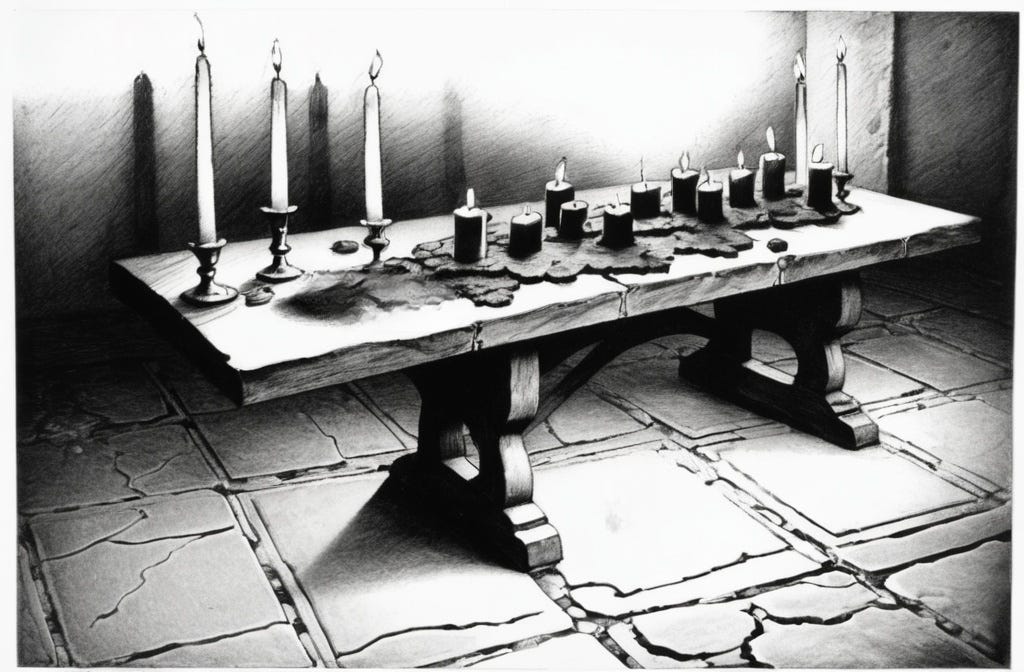

The cellar smelled of smoke and onions — the first scent strong and recent, the other a memory of former days when a merchant of Antiala had kept his surplus underneath this house. The wintry light of Mithriel’s eve, reaching in through the well of a west-facing window, revealed a space still equipped for commerce — shelving, barrels, heaped baskets — but swept and cleared for something else: A heavy table covered with candles and wax stubs, wooden chairs enough to make a ring, and a space kept open for a circle scrawled on stones in scarlet chalk.

Lomaz, properly Lomazaran bar Futara, fifth son of the paltry doge who ruled the Salman League’s seventh-largest city, was pacing around the outside of the circle, a book open in one hand and three chalk pieces clutched in the other. At intervals he would bend and make notes in the circle, in white or black or red, the chalk pieces flipping between his fingers, the letters precise against the blue-tinted stone. And all the time he was murmuring to himself, a rolling thrum of sound like a priest speaking Mandoran at the altar, except that instead of the familiar signposts there were three names that Elfred had never heard uttered in any of the orisons of his childhood – ostra’roga Haniel, ostra’roga Chamuel, ostra’roga Jerebiel, fecara set’agion, fecara set’conda …

Bless this earth, bless this night. How many times now had the youngest prince of Narsil heard his golden-haired friend roll those words out into this cellar? Enough to have passed through many different stages of sensation: An initial thrill with an undercurrent of fear, a sense of wary but increasing expectation, a period of disappointments and weariness and tedium, and at last a renewal of expectation and excitement that built to the feeling of their last preparation, on Winter’s Eve.

All that afternoon and evening everyone had seemed to share the sense that this was it, that they had supernatural momentum on their side, and all their efforts, all the small victories that had carried them along, were building to a breakthrough on the year’s longest, darkest night.

And now, five days later, what was left of that confidence? A door had been opened that night — Elfred was certain of it, they were all certain of it, what had been sparks and shivers before had felt more like a blast, and the buzz afterward had been strong for all of them. Whereas before just one or two usually had something unusual to report, in the hidden days all of them, even Drusion who never felt anything, reported the kind of experiences Lomaz called the little magic — the world seeming to bend a little to their impulses, the coincidences favoring them, and sometimes even the moments when you tried to make-something-happen and amazingly it worked.

But the little magic wasn’t what they wanted, it wasn’t why they had given over so many long nights to this pursuit, it wasn’t the promise that Lomaz held out before them, the great glittering prize.

Some schoolmen might deny it, but everyone who wasn’t blind already knew that the little magic persisted in the world, that it was available to conjurers and hedge magicians and that it was carried, in some mysterious way, by men of special destiny to whom the world gave way.

But the men of destiny drew upon it unconsciously, and if you sought it out you couldn’t do with it what the Magi of old had done; at best you might make a little extra coin with your business ventures, tumble a few more women into your bed, or perhaps, perhaps, experience a fortuitous death when you desperately needed one. And that sort of power could be obtained in less exhausting ways, especially if you already came from a family with the means to let a late-born son hang about the University of the Archangels conducting magical experiments.

So the only reason for their experiments was the possibility that the greater magic was still available — not a withdrawn gift as the orthodox insisted, not a lost science wrapped in myth as the technicals pretended, but a profound supernatural power still waiting to be claimed.

Every hermetic school had its own theory of how this claiming might take place, but Lomaz was their little circle’s leader, and for complicated reasons he believed in the theory of the lesser angels — which held that the Magi had been chosen by the Archangels themselves, that those great beings existed too far up in the empyrean to be reached by ordinary mortal voices, but that the ordinary angels in all their nameless multitudes might well be more approachable.

Nameless, that is, if you relied upon the scriptures read in the temples and shrines each tenday. But if you relied upon the Prophecies and the forbidden lore and apocrypha accumulated around them, if you assumed that all the circulating Prophetic forgeries contained at least some elements of truth — well, then you might just call upon Haniel of the moon or Jerebiel of the horses or one of a dozen other names on the hermetic lists, in the hopes that someone out there would answer to the call.

But on Winter’s Eve the door had been open, and nothing had answered their appeal. The fire, the words, the crackling power — they had broken through some invisible barrier, what had been porous before had simply dissolved, and Elfred had felt that he could see it in the midst of them, an open portal, a break in the normal world through which power was flowing into them.

And yet, and yet — though Lomaz called out every angelic name he knew, though one of after another they cried out and importuned, even finally invoking the archangels, the door remained empty of anything save its energetic pulse, and finally their own energy had ebbed, their circle had weakened, the links had broken and the door had shut.

Lomaz insisted it was a great victory. Others were less sure. What if it was proof that the orthodox were right — that the great magic was only available as a gift, that gift had been withdrawn, and so even if you threw open the door to the realm of power no angel would condescend to answer? We knocked and yelled and nobody was home, Jabarian said sourly the next evening, when they had all recovered sufficiently to reconvene — in Elfred’s apartments this time, with wet flurries falling on the Plaza of the Pump. Maybe nobody’s ever home. Maybe the door goes to nowhere.

Their leader was ready with the answer – the books and scrolls did not suggest that angels always responded immediately, but there were tales enough to show that sometimes they came, it was not impossible, how else would you explain the works of Ignan Dus in Ambardy or the healings, all in the name of Chamuel, carried out just a few years before in Port Mern …?

One might explain them by suggesting they were embellished or made up, Jabarian said, taking a long draw from his pipe.

One failure is hardly enough to make us all turn orthodox, said Gregoris lightly, in the same familiar tones that he had used to greet Elfred at Ursilon’s lecture all those many months before — and shouldn’t we take some pleasure at having gone far enough to make mincemeat of the technicals?

I haven’t been giving over all these nights to prove that fat Tomada doesn’t understand the fundaments of reality, Vardan interjected. I figured that out the first time I listened to him talk.

Usually this was where Vizalaga joined a dispute, charming and reconciling the disputants, playing the role of mother to the group, a role that Elfred hadn’t quite understood when she had first taken him to her bed. There were other women circling the hermetics but she was the only one allowed into their mysteries (though “allowed” was the wrong word, since she had been an instigator of the entire enterprise), and he had worried immediately about the jealousy of the other men — and indeed a few of them, including Lomaz, had plainly known her favors.

But apart from the special suspicion from Laidwyn, whose father was a Brethon merchant in some sort of exile from the west, mostly the resentment he felt was the kind that children might direct toward an unworthy suitor for their widowed mother’s hand — founded less on thwarted desire than on a belief in Viza’s perfection, against which Elfred was judged and found unworthy, prince though he might be.

Viza handled those resentments as smoothly as she handled everything else, and with a serenity that matched well with Lomaz’s fervor. If he burned for their project, she projected perfect confidence that its success was already written, and over time her prince-lover was enfolded into the story they were all telling one another, in which of course a prince of the frozen northern empire would be drawn into their circle and their work, as a foretaste of how magical power and real power would be soon once more be interwined. (In time, that was enough even for Laidwyn to seemingly forgive the conquest of Capaelya — though at Welsten’s stern command Elfred still contrived to avoid being alone with the young Brethon.)

Viza’s serenity about the story had stabilized them time and time again, when something went wrong or disappointed, when they entered deserts when nothing seemed to work, as well those more troubling occasions when the power flickering around them felt hostile or malign. But the day after Winter’s Eve she stayed silent while the men debated, and later that night she lay silently beside Elfred, not-sleeping in the way that usually accompanied an argument — but in this case he believed her when she said she wasn’t angry, because whatever she was radiating wasn’t an emotion that he recognized, and he wondered if it was the power that had entered into all of them, but maybe into her more than the rest …

Four days later he was still baffled. She was not herself, but also not upset in any normal way that he could recognize. They had dined with the large group once, and with the inner circle – Lomaz, Gregoris, plump Fundus, the sleek and mysterious Palermian — and each time she had been charming but recessive, a spectator not a mother. They had breakfasted with Welsten and his men. They had gone walking on the Mersana bridges in the snow and visited the Hiddenday Markets on the brighter days. They had made love once, tenderly and urgently — but that had been the only moment when she felt as close to him as usual, otherwise she was distant, not just playing around with mystery in the usual Viza-from-Azania manner but off somewhere he couldn’t follow.

He thought that he knew so much about her, she was mysterious in her affect but transparent as to her own history. The happy childhood in Abusu on the far southward tip of Azania, as the daughter of one of the concubines still kept by the great men of the city, in the tacit compromises between Azanian tradition and the Mandoran revelation. The unexpected intervention by her father, a lord magistrate, to pluck her from her training in her mother’s arts and place in a school for aristocratic girls – elegant, courtly, miserable. The books, the library, the piled-up knowledge of the southern world, as an escape from feminine oppression. The engagement, arranged of course without her consent, with an ambitious merchant from Burhara, eager enough for the connection with the nobility to accept a by-blow as his wife. The flight, with the connivance of a eunuch courtier, that took them both by ship to Nevus Albina and then Mersanica.

And then the need to go further, to escape the High King’s dominions, to reach a land where her father’s arm might not be able to follow. The way north up the Mersana, and then the idea of this university, one of the four in the known world that still maintained Abdiona’s Test, named for the intellectually-minded High King’s daughter who believed that women should study with men, and whose indulgent father had established a test for that purpose, made suitably impossible by the horrified schoolmen but not so impossible that it could not be passed by the occasional female of real genius, which meant that every year a handful of women entered the University of the Archangels on the same terms as the men. Finally, the student’s life, as just such a young woman of genius, turned muse and mother and magician in a circle of ambitious men.

Unless the transparency about her past was all just veils and flummery, a made-up tale to fit northern ideas about the south, to keep the men entranced, to lure in marks like a northern prince —

Those were the thoughts he toyed with unhappily as the winter light ebbed and the cellar darkened, as Fundus lit candles and Lomaz prepared their evening’s work, as Jabarian and Palermian murmured in a corner with Laidwyn and upstairs the servants readied dinner and he tried to recapture the sense of wild momentum he had felt less than a tenday previous … but beside him his lover sat humming in her native language, giving him glances and vague smiles but no more than that.

And above all else, more than an encounter with a lesser angel, more than a blaze of supernatural power, what he wanted was to know what she was thinking, what the open door of Winter’s Eve had done to her.

They ate together upstairs, a hearty meal as always, stews and breads and winter carrots, strong meads from Janaea, Lomaz holding court with more intensity than usual, as if to compensate for the sense of drift and skepticism from some corners of their common table. Then the servants cleared and the legionnaires Welsten had assigned to guard this night, Fredegar and Redmund, began a card game that Elfred joined for a little while, letting Viza drift off into the after-dinner circles, while he watched her from a corner of his cardplaying eye.

Not surprisingly he lost almost every hand, finally giving up and pushing the coins toward the grinning soldiers and then leaving them to their evening relaxation, their none-too-rigorous duty of keeping the house secure from assassins of all stripes.

As far as the legionnaires knew they were guarding a long drinking party that carried on in privacy, though that subterfuge had been easier to sustain when the group had switched houses each time, sometimes ascending to an upper story or a private room in one of the apartments that the richer members of their circle kept. Now that they almost always used Lomaz’s cellars, Elfred was certain that his bodyguards must guess that something occult was being attempted underneath them, and he was a little surprised that Welsten had not yet made some grumpy intervention.

Perhaps the adjutant thought of magic as one of the more harmless ways that a young prince could educate himself, and certainly he seemed pleased with the diversity of Elfred’s university friends — the mixture of different kingdoms, the sons of nobility like Lomaz mixing with merchant offspring and a even a few, like Vardan, who came from truly common stock, reaching the university through some roundabout means that involved a patron’s recognition of their talent.

But still the prince wondered — couldn’t the legionnaires feel that something more than play-acting was happening here, didn’t they absorb some of the magical leaking-out, didn’t they know they were playing cards atop a simmering volcano?

And if not, did that raise the odds that the simmering feeling was all somehow just imagined, or something that existed between them in their circle, but maybe not out there in reality itself?

That’s what the technicals believed and argued, that even the little magic was a purely subjective sensation, that the effects it seemed to have were too uncertain, coincidental, intangible to be treated as a real power in the world …

But no, there was real power here, the doubts went away as always as soon as they descended, the circle formed and the work began, including the doubts that he’d been feeling all day, the sense that maybe they had peaked already and now it would just be a disappointing descent. Their shared belief had peaked, certainly; he could feel the skepticism among them like a countervailing current. But whatever had entered them on Winter’s Eve was still there, a pulse stronger than their conscious doubts, lifting them immediately when Lomaz spoke the initial invocation, asking for blessings from the highest powers even though they weren’t directly asking them for help --

Ar’me Mithriel, ad’me Gabriel; sed sixion Raphiel, sed drixion Uriel …

Before me Mithriel, behind me Gabriel; on my right hand Raphiel; on my left hand Uriel…

— and then they were back at work, taking their turns to read and recite, the prayers and the (supposed) passages from the Prophecies and the magical invocations drawn from long hours in the nooks and corners of the Library, mostly in Mandoran but with their own native tongues worked in because of a suspicion that there might be power there as well, taking turns, passing the power around their circle like a ball, because when it was working it felt just like a game, a children’s game that sometimes made them giggle or even laugh out loud, laughter being the appropriate response to a reality that sometimes felt so ravishing as to cast all of ordinary life into its shadow, if you could bottle it and sell it in the marketplace then everyone would realize that all their everyday anxieties were unimportant, if you could only sustain it without all the preparation and exertion then they would never want for happiness

— but even with the exertion it couldn’t be sustained, they had played with it enough to know that it only rose or fell, you were either building toward something or else feeling it slide away, sand through fingers, wax pooling as the candles reached their nubs.

So as the power built, they each built higher in their own way, Fundus chanting like he was delivering the Great Orison, Drusion punctuating his readings with an athlete’s pants, until Lomaz, always Lomaz, judged the moment was right to offer the most powerful of all the elocutions they had found, the Cry of Eylandion that appeared nowhere in scripture but only in the apocryphal Mernese Codex, forbidden by the inquisitors like many of their texts but nonetheless available to those who knew where to look, and by this time committed to common memory in their group, with its escalating cadences and its culminating appeal —

Eferana ethyrion ama’erala!

May the heavens open to my call!

And for the second time it happened. If Winter’s Eve had felt like a melting-away of barriers, here on Mithriel’s Eve it was more like a pop, a little explosion, as though they were more impatient this time and the obstacles didn’t have time to gracefully dissolve. Again the opening was there, less a doorway this time then a kind of arch, or even – these were all just impressions, things felt more than seen — a kind of bridge leading away into to the lightspace, the pulsing reality that bound and held them all.

Viza’s hand was in his, brown and winter-pale fingers intertwined, and for a moment he felt like he could let go of his own self and somehow merge with hers, let the energy that flowed through them somehow unite them, so that as one mind he would understand what she was thinking, feeling, hiding …

— but something was required of him besides a melting into unity, as Lomaz led them in the set of appeals, the same idea as last time but with new flourishes added, new invocations, not just Haniel and Chamuel and Jerebiel, the targets on their last attempt, but other names, some less familiar to Elfred — Sandalphion, Metathrion — and some invoked in a language he didn’t recognize – Harvatat, Ameretat, Aratat, Adwarshit.

With each appeal there was a strong pulse, a sense that the reality beyond the arch was reacting to their importunings — but impersonally, mechanically, dosing them with the little magic as a cow’s udder might be tugged for milk. There was no active response, no personality, no voice, just the energy and light. And they couldn’t hold onto it forever, it seemed to fill them and drain them simultaneously, and as on Winter’s Eve Elfred could feel an interior slackening, a sense that even though part of his body craved the connection another part was ready to let go.

Lomaz was clearly drained, drenched with sweat, on one knee as he gripped wrists with Gregoris and Fundus, his invocations subsiding, no energy left to command the others to speak up. There was a flickering in the light. Two of Viza’s fingers slipped slickly free of Elfred’s grasp. Drusion was chanting, he had returned to the original call, bidding Chamuel come to your humble servants, your unworthy servants, and raise them up to show your power in the world. And as his voice slackened and subsided, the prince thought that this was it, the ebb tide was open them, the call had gone unanswered once again.

But then Laidwyn spoke — in Brethon, in words that Elfred almost understood, hearing through them his own mother’s voice, his lost mother, his lost world.

The words held him, held everyone, the circle strengthened briefly, the energy pulsed stronger, Lomaz from his knees looked up and let it happen, whether he intended it or not he let it happen —

… rythaida rythaer tua, rythaida rythaer tua, hy raenya frytha coelm, hy raenya frytha coelm, raenya dae’aran, raenya dae’mar, Raenya, aer Raenya, aer Raenya maebor Brethonae coelm, maebor yris coelm, coelm aer Raenya, coelm aedethyr, coelm!

A raenya was a queen, a queen, he was calling for a queen, and now Palermion joined him, the accent clumsy where Laidwyn was smooth, the words clearly rehearsed, and together they called, they called out, and now Lomaz was on his feet and Viza’s hand was gripping Elfred tightly, and someone, someone was speaking against the two men, questioning, what are you doing? what are you doing? this isn’t agreed

But then something was with them. Or someone.

For the first time the opening wasn’t just a doorway into light and energy. There was a kind of thickening, a condensation, and suddenly the bridge that he had sensed became a road that he could see — a road with paving stones, vines growing in, cracks, tree-shapes above, woodlands, strange and dark, and something was coming down the road toward them, something booted, he could hear the click of bootheels, did angels have bootheels, did angels look like this?

It was a man with a white beard, smooth features, a cloak of silver over a raiment of white. It could be a lesser angel, it was not as they appeared in statues and glass but not so far off either. Certainly there was something radiant about him, some otherworldly wisdom in his eyes.

He spoke in Brethon, sonorously, the accent beyond Elfred’s comprehension.

Laidwyn’s voice answered him, trembling like a child.

“Who are you?” It was Lomaz, he had found his voice. “I bid you speak to us — to all of us. I bid you make yourself understood. In the name of heaven, in the name, in ada’Mithriel ethyrionis ara …”

The figured laughed, then, and replied in a voice that might have been angelic — but what he said belonged to nothing in any scripture that Elfred had ever read.

“Tuathyl’a … I speak for the queen of the silver court, mortal. Who summons? Who asks? Who remembers? What is sought, and what is offered?”

“The queen …” Lomaz said, while Laidwyn fell to his knees.

“Great lord,” he said. “Dae Abaira. Great lord.”

And then —

“No! No! By all the holies, no.”

Something tore at them. No, someone tore — Viza, it was Viza, she flung Elfred’s hand away from hers, breaking the circle, stepping forward toward the other place that was somehow there with them, the road and the woods and the man who spoke for the queen, the being they had summoned. As she moved she cried out —

In conio Mithriel impera’ethyrion, An cara teririon An far sokorion. In conio Mithriel, sur ar anna, sur ar anna, in conio Mithriel, in conio Mithriel …

In the name of Mithriel prince of heaven, I break this circle. I banish you. In the name of Mithriel, on Their day, on Their day, in the name of Mithriel, in the name of Mithriel …

The speaker in the woods curled his lip, a smile of amusement, ironic in the way that no angel’s face should ever be — and then the pulse of energy ran wild through them, flaring and bursting, all unity broken, someone was screaming, Laidwyn cried out in Brethon, Elfred reached desperately for Viza.

Then with a weird geometrical precision, like a quilt quartered by an invisible servant, the portal suddenly folded up on itself and vanished.

The fires had all gone out, the cellar was in darkness. There was panting, grunts, curses. Someone lit a candle — it was Fundus, his face illuminated like a surprised ghost. The light spilled over the scattered chairs, the chalk markings wiped away and the floor blackened — seared? — in the middle of the circle, the few of them who were still standing, the rest on the ground.

Laidwyn had his face in his hands. Palermion was staring thunderstruck. Elfred found himself on his knees, one hand gripping Viza’s skirt where she still stood, arms outstretched like wings, frozen like an angel on a plinth.

Lomaz pushed himself up, shook sweat from his golden hair, and stared around wildly. His gaze lingered longest on Laidwyn but it was Viza that he went to.

He gently brought her arms back to her sides, even more gently kissed her on the forehead, and as Elfred scrambled up he heard their leader say to his lover,

“You did well, my lady. You did right.”

In the cold morning light they sat together in the Plaza of the Pump, sharing the rim of a fountain that Elfred had swept clear of snow, watching a few crows peck their way across the icy stones.

In the cellar the argument was probably still going — the rage at Laidwyn and Palermion for daring to traffic with what, with fairy spirits?, the fury that they had planned this on their own without general agreement, balanced against the excitement that some kind of being had actually responded to a summons, had proved that someone would answer to their knocking, that their doorway wasn’t merely a dead end.

But after she had spoken quietly with Lomaz for a little while, Viza had taken the Prince of Narsil by the hand and led him up and out, away from the rest of them, into the night’s wee hours and back toward the lodging that they shared, his bodyguards trailing sleepily behind.

Now fortified by warm drinks from their kitchen, she leaned against him where they sat, her cloaked body and their closeness reassuring as his mind circled back again and again to the circle, the power, the summoning, and that last look, inscrutable and somehow unforgettable, from the bearded face before its world folded up and vanished.

You might as well summon the Damned! Vardan had been shouting with when they left the cellar. But it wasn’t a demon that had come to their call, it was something else, something that for some reason made him think about his family for the first time in angels knew how many days.

Maybe it was just the connection to Brethony, his father’s conquests, his brother’s war, but the wood that opened behind the man in silver who spoke for the silver queen — hadn’t he seen that somewhere, in a vision or a dream? Hadn’t he seen Padrec walking there, and Alsbet too? Or was his sleepless mind just playing tricks —

“I’m going to have a child,” Vizalaga said softly.

His mind took a few more circuits through the cellar and the circle and the night just past before she realized what she was telling him.

“I’ve known since Winter’s Eve. When the door opened, when the power went into us, when it burned so strong — I felt it go into me and into someone else, someone inside me, in the heart of me. I’ve felt it all the hidden days. I feel it now. I’m sorry, I should have told you quickly. Our child, Elfred. Ours.”

The play of feelings on his already-confused mind was rapid, intense, difficult to map.

There was joy — he loved her, of course he loved her, this was what love yielded, a child of his own loins, a future for them both.

And there were different kinds of fear. For Elfred the student, Elfred the would-be mage, there was fear of loss — of losing this life, their circle, their quest, Viza’s central role (how could the mother of his child traffic in magical summoning?), his entire way of not-being-a prince.

For Elfred who was a prince, there was the fear of judgment, what Welsten would say or what his father would say, what would become of the child if it was a bastard and what would happen to him if he made sure that it wasn’t. And also the fear of everything he didn’t know about his lover, his woman, the mother of his child.

He bent his head and kissed Vizalaga, his mind still whirling, because there was nothing else to do.

She began to speak again but just then behind them the great door of the apartment building creaked open, and Welsten appeared in the cold light. The soldier hesitated briefly at the sight of their embrace and then crossed to them briskly, his boots sure on the ice. His face was gray and unshaven, his eyes unreadable.

“Highness,” he said.

“Adjutant,” Elfred said, wondering if the night’s events had made some especially strange impression on the soldiers, wondering if they had roused Welsten with wild stories and finally they were going to have some uncomfortable conversation about magic.

“I thought to let you sleep after the night’s revels, but if there’s no sleeping being had, well —” He paused and eyed Viza, and then, as if something had been decided in his own mind, went on addressing both of them:

“The bird came last night with the news. Your imperial father is dead in Rendale. Your brother is to be crowned. And there is no suggestion this time – you, my prince, are summoned home.”