This is Chapter 18 of The Falcon’s Children, a fantasy novel being published serially on this Substack. For an explanation of the project, click here. For the table of contents, click here. For an archive of world building, click here.

“And when the One Who Is had withdrawn into the empyrean, his children the Archangels created the spinning stars and placed them in the firmament, and set the sun and moon to wax and wane above the green fields and life-giving water. And then they made man and woman, the first of our race, that all might dwelt together in peace, mortal men and immortal angels and the thirteen Archangels, and all the earth was young and fresh and abundant with good things . . . “

The pews were hard, and chilly, and the braziers smoked and smelled sticky-sweet with incense, and behind the seated nobility the masses of standing people shifted and scratched and hushed their babies and quieted their dogs as the archpriest droned on laboriously, his chins jouncing and sweat beading on his hairless head.

" . . . and the Four said, ‘let us make these mortals our slaves, and after death let us keep their souls for our own, to serve us for all time.’ And the Nine opposed them, saying: ‘these mortals can be raised to an immortality that is like unto ours, therefore they must be our brothers, and not our slaves.’”

“Blessed be They forever,” the multitude said.

“Let us name the Nine: Mithriel, Prince of Heaven.”

“Blessed be They.”

“Gavriel, Prince of Heaven.”

“Blessed be They.”

And on, through Raphiel and Jophiel and Zadkiel and Abdiel and Raguel and Uriel and Azriel, nine “blessed be They”s, and Archpriest Ethred paused and bowed his head, and his scalp gleamed in the light of a hundred flames. The people bowed, too, and some of them prayed and others lost themselves in the privacy of thought until Ethred spoke again, telling of the war in heaven, and how the Four were cast down, and how they took up their abode in Abaddon in the uttermost east.

“Damned be They forever,” the masses said.

“Let us name the Four: Aeshma, Prince of the Abyss.

“Damned be They forever.”

“Baphama, Prince of the Abyss."

Baphama was damned eternally, and so were Molokh and Lelet, and Ethred shifted ponderously and told the congregation how the Damned had enslaved the race of men — seducing Cais, son of the first parents Eris and Era, beguiling his heirs, and casting a darkness over all the earth. And how the Archangels had descended, and scattered the darkness, and broken the chains — all for the sake of the righteous remnant, the slaves who remembered their creators.

But even in defeat, bound in Abaddon until the changing of the world, the Damned still had the power to send their spirits abroad and spread evil throughout the world, spread idolatry and superstition and heathenism — here the archpriest directed a significant glance at the Bryghalans. And even after their rescue, mortals still accepted gifts from the Damned, still were taken by sin and given over to war and wickedness and unnatural lusts, until the world was stained, even to this day.

"So the Archangels chose the first priest, and the first mage, and the first high king. And the first priest, our first Father, began to write the sacred books, containing all History and Law and Prophecy, that we might be led out of sin and error. And from his disciples came the nine orders, to shepherd our souls out of darkness into light.”

“Blessed be They forever.”

Standing with her sisters, all of them unveiled and hidden behind the intricate screens that enclosed the choristory, Fidelity thought that it was strange, so very strange, to hear the same passages that marked the turning of her childhood years in Balenty reverberating here, in such pillared vastness, with such crowds, such resplendent nobles, such smells and lights and colors as would have once left her old self stunned and breathless, and even now still had a dizzying effect.

Now the introductory rite was over, Ethred was seated and the Greater Orisons began. The gold priests started first, the deep chant, and then a few of the sisters wove their brighter voices over the deeper pulse — Devotion leading, of course, and then Felicity and Beatitude, the Mandoran harmonies spiraling and then diminishing, the ordinary music of a tenday raised to something more transporting.

The prior year Fidelity had spent Winter’s Eve in the sisterhouse chapel with Temperance and the other aspirants, preparing for her elevation to the sisterhood. Now she was in the back row of the choristory, just one small voice among many, but when the trio of sisters made their invitation and the full choir responded, she sang out lustily and thought of the moment in her vows when she had pledged to join the earthly body of Holy Jophiel, for we are the holy one’s hands and feet, Their ears and eyes, heart and mouth. In this moment that vow was fulfilled, they were many parts and one body, many sisters and one voice, Jophiel on earth, the archangel’s spirit in the flesh …

Then it was done, the last notes hanging, echoing, gone. The great chair groaned as the archpriest rose, two acolytes scrambling to assist him.

Through the screen Fidelity could see him swaying slightly as his rich vestments sparkled with reflected light. Then he spread his arms wide.

“My friends. My friends.”

The words echoed to the corners of the temple, seeking to embrace them all, from the beggars in the doorways to the emperor himself. Dukes and merchants, ambassadors and fishmongers, Aeden and Padrec, Alsbet and Maibhygon, priests and sisters — the Archangels looked upon all of them with favor this night.

“… my friends, the Nine gave us the precious Law. They freed us from the immoralities and abominations of the former world. They told us that if a man shall take a woman to wed, and they pledge in the sight of heaven to cleave to one another even unto the grave” — and here Ethred lifted his voice with all the strength that a sweating fat man could offer — “then they shall be blessed.”

Behind the nobility, the standing throng thrummed approvingly. The same thrum ran through the sisters, through Fidelity, as though Alsbet’s marriage was their own.

“Tonight . . . tonight is Winter's Eve. Tonight we shall seal a man and woman together, binding them with prayers and promises, so that when the hidden days pass, and the Feast of Mithriel, they can be sent forth from our city. And in three months, in a far-off land but still under the sight of the Archangels, the Princess — our Princess will take that most sacred of vows, will enter into marriage. On this night — on this night, we gather to celebrate her betrothal.”

Ethred paused as the congregation rustled and waited expectantly, and outside wind wasted itself against the temple’s walls. Then the bells began to ring, reverberating high above the mass of people, marking day’s end and the true Eve’s beginning.

“Let the couple stand forth.”

Afterward — after the first sealing, after the sacrifice, the smoke from the ewe’s body rising to form a cloud bank in the temple vault — the city celebrated. The snow was falling softly as Rendale’s people departed the temple, the cold delicious after the sweat and incense within, and children ran laughing through the twisting flakes. For a space of time everyone was happy, it seemed — all the anxieties of the strange betrothal temporarily forgotten, because it was hardly every day that a lovely princess was betrothed with pomp and circumstance to a handsome foreign prince, and weren’t the nobles dressed so fine, and weren’t the two a handsome couple?

And now it was the Eve in earnest, a time for feasting and singing and more ale and cider than a man had a right to, with the fire banked high and someone playing a zither as the young men and women danced, the children fought with snowballs outside or wooden swords within, the married folk relaxed and the ancients recalled the holidays of their youth, and the carousing continued long, long into the night. Even in the sisterhouse there would be a feast, the aspirants breaking their fast and the sisters tucking in to roasted meats, a rare glass of wine for everyone — but not so much, not so much, because the later hours still waited, the turn of midnight, the orisons that answered the dark and prepared the way for the new year.

In the Castle, the flames leapt in their pits as the servants weaved among the long tables, hoisting trays piled with roasted fowl and crackling breads, dumplings and deep-dish pies and pitchers of ale. Under Alsbet’s hand other holidays called for attempts at elegant, civilized feasting, but on Winter's Eve the cultured ambassadors were expected to endure the boisterous spirit of the north country, as the empire’s lords ate and drank and shouted cheerfully amid thick smoke, trailing holly, discordant music, and from the edges of the hall even the barking of the hounds.

At the high table, dominated by a small replica of the Falcon Throne where the emperor sat between his daughter and her betrothed, order prevailed for a time. Edmund was flushed, the bloom of red seeming out of place on cheeks that sank away beneath his hollowed eyes, and he fumbled with his wine glass and laughed a little bit too loudly at the sallies. Alsbet had a protective, white-gloved hand on her father's arm, but for once there was no worry in her eyes — on this night, she blushed and talked boldly and darted glances at a gravely smiling Maibhygon.

Padrec, a few seats down the table, also watched the Brethon prince, his eyes flat and unreadable in the yellow torchlight. The crown prince was flanked by two of the emissaries invited to the high table — the ambassadors of Great Salma and Janaea, a cadaverous lord and an urbane, experienced noblewomen. Across from the Salman emissary, the archpriest was doing justice to his reputation for gluttony and chatting with the Trans-Mersanan ambassador, a slender count with restless hands. Past them, facing one another at the table’s end, sat Arellwen and Benfred — the chancellor bending his head leftward toward Ethred, the emperor’s cousin alone and silent.

Down the other end of the table, five dukes of Narsil and two dukes-to-be sat together, with Cresseda a pleased cat in their midst. The weakest, Cymrin Dolwyden of Angheryd, made desultory conversation with Aedevys Aerghen, heir of Naeseny’r, who like him had traveled the long way from the Brethon lands to watch their new ruler give his daughter to a Brethon prince. Both men looked uncomfortable, but the faces around them had an obvious avidity. Some were surreptitious in how often they shot glances down the table — like Jonthen Cathelstan, whose mouth was at the ear of Greenhaven’s duke even as his narrow eyes darted toward Edmund. Others were more obvious: Eldred Gerdwell’s startling blue eyes simply bored their way toward the imperial family. But all of them, from Greenhaven’s Cethberd to Erona’s Baldwen to young Coallen mac Cree of Ysan had an unusual energy about them, a sense not only of their own importance but of this night, this feast, as a doorway into possibilities.

Treason, though, was a cold word, heavy with the bone-deep chill of dungeons and the freezing finality of the headsman's blade. It took a brave man to think of treason without a shiver, and a braver man to plan it without a vision of ravens circling a beheaded corpse, black wings beating in the mountain air and black beaks pecking …

Yet even so his fellow dukes were feeling brave tonight, Benfred thought. They were watching and pondering, pondering and watching, and some of them, maybe, were beginning to push aside their fears and make ambitious plans.

But too late, too late. Fear had kept them cautious long enough, and now any scheming would mean exactly nothing — because he was going to get there first.

At least that was what Benfred wanted to believe, with precisely that insouciant confidence, as he watched Cresseda exchange pleasantries across the birds and sweetbreads and wine. He wanted to be the kind of plotter who never made empty boasts, who was confident in his ability to see many turns ahead, who could greet any apparent setback in the game by playing a crucial, devastating card.

But he was acutely aware that really he was a different kind of gambler — a low-stakes player who suddenly decided to risk everything at the Great Casino in Antiala, and who further had decided to make his once-in-a-lifetime play by simply shadowing a richer and more confident player and hoping to rake in a portion of her pot.

There was no way to know whether that player maintained her apparent confidence in the private garden of her thoughts. But he was here tonight, sitting a few spans from his cousin and committed to a plan to overthrow him, because Cresseda seemed to have no doubt whatsoever about her capacities. He had allowed himself to be carried forward by her confidence — and now here he was on the cusp, aware that when they leaped she would be pulling him along, across the abyss to the other side or simply down and down and down.

She was laughing now at some joke from Coallen, while Cethberd leaned toward them to make a point, and for a moment he recalled the resentment he had felt when he realized just how far back all of this went, how patiently the Argosan dukes had worked to use their silver (from the mines left to Argosa after the conquest, in a gesture of stupid Montair magnanimity at a time when new gold seams were still being discovered in the Guardians) to buy and befriend and seduce and corrupt, how contented they had been with the long view, in which even the ill-fated marriages and betrothals of his youth could be treated as modest plays in a very complicated game.

It was silly and childish but the sting of that revelation was really the only moment when he really imagined himself doing as Cresseda had once suggested he might, and going to Edmund with the plot and claiming to have been acting secretly on the emperor’s behalf. It wounded his family pride, the knowledge that all this could have gone on without the crown ever realizing, without his cousin or his uncle or his grandfather ever doing anything about it, gone so far that even the emperor’s spymaster was actually bought and paid for by Argosa —

Benfred flicked a glance lower down, to the table where Lord Rell sat with other members of Edmund’s council, thinking about that one small detail among the many that Cresseda had offered him, the realization that when he had sent worried letters to the Lord of the Secretariat he had been writing to the iron duchess’s cat’s paw —

And how do you know that Lord Rell isn’t running his own game?

Benfred, when I buy a man I always make sure there’s a reason that he’ll stay entirely bought …

— and there again was that astonishing confidence, which he told himself was justified by her years of rule in Argosa, and by the fact that he had always considered himself a man of information, with a few spies of his own and an interest in the empire’s gossip and yet he had never realized how widely the Verna web was spun. So if he didn’t know, wasn’t it reasonable to assume that neither Edmund nor the rival dukes knew either, that nobody would see this coming until they were all prisoners …

Our prisoners. It was quite a thought, enough to pull Benfred out of the labyrinths of anxiety. All those powerful men sitting around the laughing Cresseda, darting their eyes toward their flushed and aged-looking emperor — all those dukes and ducal heirs would be in their hands, completely in their hands, before the hidden days were out.

If the plan went well. If Cresseda was right. If the Old Hound’s men accepted his orders. If her silver bought what she supposed. If his own men played their part …

“ … something weighty, Lord Benfred?”

It was Arellwen across from him, the stolid chancellor, his question half-lost in the noise.

“I apologize, my lord, I didn’t —”

“I asked if you were thinking on something of great moment?”

Benfred reached mechanically for his wine and tried a rueful smile. “Sadly my mind was on revenue, nothing higher. The dock tithes from the summer — my little city lost a deal of coin when the greater cities closed their docks this spring, and it appears my own coffers will need to be raided to pay Meringholt’s watch through the winter …”

Was this dull enough? Was it too dull, suspiciously so? He rattled onward, uncertain where the balance lay.

“Ah, well, I was just wondering if you were pleased or displeased with where we find ourselves,” the chancellor said easily, when there was a break in Benfred’s ramble.

“Well, I’m pleased, of course — for Alsbet and her prince…”

“Certainly, so say we all! But I was thinking more of your long-ago skepticism in council about the plans for war in Brethony. Do you feel vindicated? I appears that our emperor has at last come around to your perspective …”

Benfred glanced toward where Maibhygon was sitting … except he wasn’t there, the prince of Bryghala and the princess of Narsil had descended and were making their way graciously among the lesser nobles, exchanging greetings, raising glasses, meeting more cheers the lower down the hierarchy of the hall they went.

Arellwen followed the movement of Benfred’s eyes, and smiled. “It’s not a question I would ask if the prince were beside us. But I’ve wondered for many months what you make of our situation. Indeed, I have wondered” — he leaned closer — “if you have ever thought of rejoining our council. I think our emperor needs support in ways that perhaps exceed the tithes of Meringholt in their importance for your house.”

A small part of Benfred suddenly felt that the chancellor somehow knew of his treachery, and was baiting him with this talk of what he might do for Edmund. The larger, saner part lifted an eyebrow and spoke as if it was an interesting suggestion which he had not sufficiently considered.

“But my cousin was never overly taken with my counsel, and he hasn’t offered any sign to me that he wishes for it again.”

“We are honest men, you and I,” came Arellwen’s return, “and I think I can speak plainly and say what you already know: His majesty’s wishes are not the only thing that matters to the empire at the moment.”

Even a year ago this would have been what Benfred wanted to hear – an acknowledgment that Edmund Montair was no longer the great man, the all-conqueror, and that he, the oft-forgotten, always-underrated cousin might have wisdom to offer to the empire.

And doubtless Arellwen guessed as much — so he had better act as if it were still what he desired.

“If my services were required, Lord Arellwen, I would certainly be willing to serve again.”

The chancellor nodded tightly. “I had hoped so. Perhaps we might speak again of this, once the betrothing days are done.”

Now there was movement down the table — Padrec rising, coming down along behind the ambassadors while below the servants moved past him with the next course. There were more cheers for Alsbet and Maibhygon from the lower tables, a pounding of flagons somewhere in the smoke, and the crown prince passed Arellwen and Benfred without a word and descended, stumbling a little, a cluster of servitors parting to let him pass into the throng.

Benfred hadn’t said anything, but Arellwen spoke as if he did: “Yes, his imperial highness would be one subject of conversation, without a doubt.”

The Duke of Meringholt replied with something cautious but agreeable and drained the dregs from his goblet. Another cheer went up – was it for Padrec?

Will they cheer for me?

It was indeed for Padrec — from Dunkan and Paulus and Elbert together at a table, seated with a few other young lords and some of the Castle’s more eligible ladies-in-waiting, all flush with the excitement that attended minor nobles elevated through proximity to a princess or a prince.

He wanted to join them, but he knew where he was going, and so he shook hands and kissed hands and then passed on, accepting bows and courtesies from the other tables, doing his best, as he had done all summer, to pay particular attention to the ladies who had come with their ducal fathers, to plump-cheeked Eleda Gildenfold sitting surrounded by her brothers, to the eldest Gerdwell daughter, the chilly Dredwa, and — just to appear unpredictable and desirable — to an attractive older woman with a certain reputation, the twice-widowed, thrice-married Agetha of Benholt …

“Headed for the pisspots, Padrec?” Elbert shouted after him, and he shouted something back about strong drink going quickly … but he wasn’t drinking much and he wasn’t headed out to piss.

There was an empty seat in the hall behind him, at one of the higher tables, and when the prince saw it empty he had waited five minutes and then risen in his turn.

He passed through an archway and then another, out of the hall, the noise diminishing, a servant cleaning up someone’s vomit in a doorway, lovers necking in the shadows, the soft sounds making him think of all the soft bosoms that had been placed before him, tastefully but insistently, in cities and keeps the empire over. The ladies who wanted to woo him and win him, and the ladies who just wanted to bed him, thinking an imperial bastard might be better way to rise than simply marrying some affable young lord — or thinking, in the case of Agetha who had bedded him, that the power of an imperial mistress exceeded what most men could imagine.

The reputation of the Montairs cut against such hopes: The men of his house had a reputation for romance and chastity, or lovesick stupidity and priggishness if you preferred, and in the last century there had been only one notable bastard and no powerful mistresses in his father’s or grandfather’s or great-grandfather’s courts.

But every generation was different, his blood belonged to the strange west as well as the chilly north, there was no reason that an ambitious young woman shouldn’t try …

He touched his breast as he left the halls and climbed a staircase toward the parapets. There was a letter there, folded and secure, and the fact that he kept it there was proof that if he was perhaps a little lustier than his father had once been — though who could say for sure what his father had been? — he was still a Montair, with enough romantic folly to think often, too often, of the distant Cat instead of the beauty and political advantage offered in Ysan or Erona or the Heart.

The letter was the first he had received from Caetryn since he left Brethony. After several years in which he had grown used to her presence, her pressure, her advice, she had evaporated, departing with her brother and apparently running their new estates contentedly while his father was making a marriage that pushed all her grand plans for Hy Brethony out of reach.

Padrec had written her only once, because after all a prince shouldn’t really write to a minor noblewoman and certainly couldn’t do so repeatedly without reply. But she was ever in his thoughts, and he couldn’t control the stab of joy when he returned to Rendale in the autumn after his grand tour and found her letter waiting for him.

He had opened it, breaking the outer wolf’s head seal, and found within … another sealed letter, another wolf’s head. But on the inner letter, instead of his name, was scrawled a sentence, a Brethon sentence, in what he knew was Caetryn Rhedryon’s own hand: Aebeden meherain dyrren Ref’ewer.

Not to be opened until the depths of Winter’s Eve.

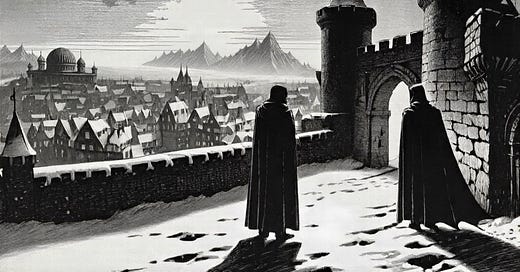

It was still sealed now in his inner pocket, as he came out from the stairwell onto the battlement. The snow was flurrying lightly and there was a thin crust beneath his boots. The man he was following stood looking out over Rendale, a net of lights from which the sound of singing rose.

Aengiss heard him coming, turned. “Well met, highness. I am sorry I did not arrive before your imperial duties consumed you. I trust you are enjoying the feasting?”

“I console myself that I am enjoying it only a little more than Prince Maibhygon,” said Padrec. “My father dotes on him as one might on a child, and the prince at least has the good grace to look embarrassed.”

“Ha! I hope you were not so sour on your travels this summer.”

Was this to be just another chiding? “I did as you recommended — I played the suitor, played the prince. I don’t know what fruit it bore.”

“It bore some. I heard a few good reports.”

“Reports?”

Aengiss spread his hands. “I do not have the spies of Argosa but legion gossip has its uses, and I have always made sure that a great deal of it comes to me.”

“So they told you that I did well enough that there won’t be a rebellion this year? That I’ve bought myself another ninemonth to watch my father act the fool?”

The old general was silent for a moment, and Padrec braced himself for some withering comments about playing the man and growing up and more —

But instead Aengiss cast a glance down over the celebrating city, brushed some snow over the parapet, and said quietly: “No, they don’t. They tell me that your throne is in grave danger, and right soon.”

Suddenly the winter air felt colder.

“From whom? From which duke? What have you learned? What must we do?”

The older man shook his head. “For tonight, I need you to do nothing except trust me. Do you trust me, Padrec?”

“Do I trust you? Of course, why should … Aengiss, just tell me! Whose plot is it?”

“Do you trust that I love your father? That I believe him to be a great man, a great emperor whose name will be remembered with honor for generations yet to come?”

“A great man — is that what you think? I thought you think as I do, that he has fallen into — that he has become foolish … what does this have to do with the plot?”

The general’s hand snaked from his cloak and seized Padrec’s wrist. “I can believe that your father was a great emperor and also believe that his time has passed. Do you believe that as well?”

“Do I believe … I don’t know what you’re saying, Aengiss.”

“Do you believe his time has passed?”

The wind gusted. There were flakes of ice in Padrec’s hair.

“You know I do.”

“And you love the empire as I do, beyond personal attachments, beyond even your own life, your own life or any other’s?”

There was some echo of the oath of coronation there, Padrec thought — dimly remembering his tutor’s recitation. Some echo, but why …

“Yes, yes. Yes. I love the empire as you do, Aengiss.”

“Good. Good. You must. You must.”

“But this plot —”

“This plot — listen. Your father cannot stop it. Only you can act as the empire requires. But there still are things I must find out, things that I must do. So I am here asking, at the year’s ending, in the sight of heaven — will you trust me to serve you?”

Their gazes locked, held. Padrec felt that he was being asked some terrible, decisive thing, but with a mind too darkened to fully understand the stakes.

So he said what he would have said as a soldier, as the adjutant to Narsil’s greatest general —

“I will trust you, general.”

Aengiss smiled then, and his hand went across to Padrec’s shoulder. “Thank you, my prince. Now you must return to feasting, and by all the angels get yourself to an early bed. And let me work.”

“Work – for how long?”

“I promise you that before the hidden days are out, I will convene a council of war, and reveal everything I know.”

“Am I in danger now?”

“No, I think not. Not this night. But soon, yes. Which is why I have to take the steps that you have given me permission to take. And then we will understand more.”

Padrec hesitated, unsure of what to say. Aengiss suddenly bent and kissed his hand, a gesture that he had never made before.

“Let me return first,” the Ysani soldier said. “Wait a few minutes before you follow.”

Then he was gone, leaving the prince alone with the flurries, the cold, the city spread beneath. His mind ran in circles; he had done something here, but what? What was in motion? What was happening around him, beyond the torchlight, in the dark?

Below a single firework flared over the city, a flower in the night.

“I do love the empire,” he said at last, unsure of what he meant, and then he absently touched his breast, touched Cat’s letter, and went in to the feasting and the warmth.

In the great hall they had reached the desserts — Ethred was already working his way through a second slab of golden, sugar-gleaming apple tart — and Arellwen had descended from the high table, offering his chair to Guernys, the prince’s white-haired seneschal. She left her seat at a table filled with Brethon knights while he went down to join his wife, come from Carn Maal as always for the holiday, and his son, given leave by Lord General Veruna to come south from Caldmark for the feast.

They were sitting close with Secretariat and Exchequer — the bachelor Rell alone and the uxorious Clava with his golden-haired wife Titaria, who unlike Arellwen’s Merida preferred to live with her husband in Rendale, leaving their large estates north of Argosa to the management of Clava’s several sons.

Titaria had been her lord’s mistress for years before their marriage, and rumor had it even a courtesan before that. Merida disapproved of her officially, as she officially disapproved of everyone at court — she was just a simple country mouse, she liked to say, and the cats here would eat me up — but when they encountered one another she obviously enjoyed her company, and the two women were deep in friendly conversation when he joined them, his wife’s plump face flushed and laughing in the way he always liked to see her, the way that gave him peace.

Whatever I’ve done I haven’t hurt her, he always told himself when the weights were on his conscience. My sins are my own, I’ve kept her safe from them.

Further down the table was a mix of neighbors from the Moor country and some more important Ysani thanes and earls, and he could hear the familiar thrum of conversation, in the familiar accents of his youth — talk of younger sons far away in Brethony and daughters who wanted to make unsuitable matches and the flooding around Carstaar Pond and the old familiar jokes (we couldn’t very well invite a pond to sit with us … a foot in the grave … my Camden would take half your land in the heartbeat if you did …) and let it all comfort him, ease his anxieties, remind him that though the summer had been hard and the emperor was failing the empire was generally at peace and the people generally content, and any plotter wouldn’t have all that many discontents to work with if they tried to move against the throne.

He reached for a pastry, bit and chewed as Merida put her hand fondly on his arm. A general peace, and a year without any further price for his private evils. A full year and more to hope the horrible night in the House of Birds was already the punishment, and not as he had feared the beginning of some larger unraveling. A year in which his choice to keep the girl close had yielded nothing in the way of scandal. And the first year in twenty when he had not gone to the Day of Atonement and confessed a sin against the innocent — indeed a year when the thought of innocent beauty no longer stirred him so unbearably, but only reminded him of the stink of vomit in the basin.

Across the table his son Lethen was talking loudly and cheerfully to the other Council lords about Caldmark and the border country, the real north as folk there called it, where he was stationed for another year –

“… cold as the lowest hell,” he was saying. “And I thought it was cold fighting in the north of Allasyr. But I don’t mind it, it’s good to be in a place where you know your enemy, where they show up in blue paint and screaming instead of slipping you a knife while you’re buying apples at a market. And I’m happy to be anywhere with the Old Hound — with Lord Veruna, I mean, sorry, that’s just what the lads call him …”

“That’s what we call him in the council, too,” said Rell with an easy chuckle.

Lethen nodded brightly. “I know they say Aengiss, Lord General Cullolen I mean, is the great genius, but I wonder if his men can love him the way we love Lord Veruna. I’d pick Lord Cullolen to draw up battle plans, but if you want a commander to make men believe that he loves them and protects them it’s the Old — it’s Lord Veruna all the way. We’re going to retire together, they say — my five years are up next autumn …”

“Thank the angels,” Merida murmured to her husband, an aside from the chatter of the wives.

“… and he’s pledged that he’s going home to the south when he turns sixty years next summer. The cold makes him ache, he says, and he doesn’t want an easy Heart command! But I don’t know if I believe him. All these generals, after forty years, what do they know but soldiering? It’s good for me to get out now, else I’d never be able to settle down to stewardship and farming.”

“I’m sure Lady Murwen will be happy to have her husband no longer in arms,” said Rell.

“Aye,” said Lethen, “and little Arell even happier!” Murwen was Lethen’s bride, the youngest daughter of Mabon’s duke — a great match given their station, made only because Arellwen was chancellor, and now she had given his son an heir who bore Arellwen’s own name. That was part of how he endured the intrigues and the fears – the gains for his sons were so tangible, the legacy so clear …

“… be glad I was sent north this last year, too. There’s been more fighting on the border than in Brethony since the treaty, so I get my last combat bonus, my last taste of your treasury’s gold, Lord Clava!”

Exchequer’s eyes twinkled. “I still have enough of a hand in to the river trade that I might be able to advise you on how to spend it, Lethen.”

“Well, Murwen will have some thoughts on that — I think she hopes I’ll put a daughter in her — I mean that we’ll have daughters, sorry, mother — and she always talks about the dowries we’ll need to see girls married. And she always jests about father helping smooth our way to marrying into some of the Heart families, and I don’t think it’s all a joke.” He smiled with the practiced rue of a married man. “But I tell her father has enough on his mind keeping the empire together, that he’s too busy arranging Montair marriages to worry about girl-children we haven’t even had.”

Arellwen shook his head. “When the girl-children come perhaps I’ll be happily retired, ready to play matchmaker.”

As you played matchmaker with one girl already, marrying her to holy Jophiel, standing in the stead of the father your own man butchered …

A swell of music buried the voice of self-reproach, as harpers moved between the tables. A jester tumbled after them, a fool in black-and-white motley, patches and bells with a half-charcoal mask painted on his face. Arellwen did not know him — he was not Edmund's court fool, a lanky fellow named Trajian who hailed from Great Salma and was juggling somewhere in the smoke. But for a moment their eyes met and the fool smiled, as if they shared a secret.

He must have come with one of the dukes … and then the jester somersaulted away, to cheers from a group of Heart ladies in a table further down the hall.

“… don’t mind because I’m out soon anyway, but the men who expect to soldier for another stint or three aren’t happy. Am I allowed to say that, father? It’s just grumbling, no more. You must know all about it, Lord Rell, with your spies …”

This was more dangerous territory, and he wished his son would go back to talking about battles and blue-painted Druanni. But the other Council lords were pressing him, and so he went on talking about the legions and their discontents, the mystification in the ranks when there was peace with Bryghala instead of war, until finally Arellwen interrupted:

“If you’d like to make a report to the full Council, Lethen, before you ride north again, I’m sure that can be arranged. But perhaps not here tonight.”

“What does the Old Hound think of it?” Lord Rell said, as if Arellwen had not spoken. “I know you aren’t one of his adjutants but word of his moods must get around.”

“I mean, I don’t hear it from his lips, but he doesn’t like Brethony — calls it fairyland, calls the wars there Aengiss’s war, sometimes, I’ve heard. So I don’t know if he’s all that unhappy not to have another war there ahead of him — if he weren’t retiring, that is.” Lethen rubbed his jaw, where a smear of sugar sparkled. “Anyway I think he’s mostly worrying about the border, these days, though nobody’s sure why …

… So I had the fellow sacked! I mean, the nerve of it, suggesting that I don't know my own herds! More familiar voices from further down the table, still comforting, like Merida’s fingers on his hands. Was he ready to be old? Ready to be a good man, not the public power broker and the secret sinner? If he could get Benfred and Padrec both on the Council, let the son and the cousin manage the emperor, let the Montairs deal with their own problems for a time …

“… he thinks there will be more raids so late?” His wife had been drawn fully from her own conversation into theirs.

“Don’t worry your mother, lad,” Clava said. “We’ve heard nothing on the council of stirring since the summer, have we, Orfenn? No hint of a winter war?”

“No hint at all, thankfully,” said Rell.

Lethen shook his head. “Maybe it’s just some exercises, then — he’s just pulled men back from the borderforts to Caldmark, more than usual for the winter, and set more patrols behind us, down this way. Talk is that he’s worried about the bluefaces slipping past us, though nobody I’ve talked to has seen anything. But he’s got a good nose for trouble, so …”

“A hound’s nose?” Lady Clava interjected, to polite chuckles.

“It doesn’t sound that important,” Rell said easily.

“Well, we ought to hear if he’s actually worried,” Clava said. “After we’ve slept off this night I’ll mention it to Borkji, have him send a bird — or a message with you, lad, depending on when you’re leaving …”

Clava was right, the maneuvers sounded odd and they should know what Veruna was about — but Rell was also right, surely it couldn’t be particularly important, not compared to the other anxieties afloat in Arellwen’s thoughts. So he put it aside and raised his eyes to the high table, to the various Montairs scattered down its length …

Benfred on the council. That was the first move, and there would have to be more, starting with a marriage for Padrec, who could stay here in Rendale longer, maybe, if this marriage really kept a Brethon peace —

And why shouldn’t it? Perhaps because he was drinking a little, perhaps because of the smoke and warmth, Arellwen allowed himself to feel slightly optimistic, there with his wife and his handsome son, while around them the singing rose and fell, now in tune and now discordant, the music of a happy Winter’s Eve.

At the high table seats been rearranged for the last serving of wine. Jonthen and Baldwen were arguing insistently about some unimportant piece of history; the ambassadress from Great Salma was flirting, in a methodical way, with young Coallen of Ysan; Cethberd was half asleep in his cups; Cresseda was carrying on a conversation with the two Brethon lords that both seemed eager to escape; Benfred had descended to visit the lower tables. Alsbet was next to Padrec, asking him about his summer travels, talking seriously about the marriages that he might make in tones that called to mind their mother, which made him want to snap at her, to spoil her happiness by telling her what Aengiss had just said to him, that their house was in danger, that her betrothal might be the excuse for some great treason …

… but instead he tried to turn part of his attention away, to listen for hints of the mysterious plot in the conversation around the imperial table. And at just that moment Ethred’s voice rose drunkenly, addressing Maibhygon in tones that came close to a harangue.

“… but surely, surely, you do not wish to live in superstition?”

The Bryghalan prince returned, in slow and formal Narsil, that what the archpriest called superstition was the faith of his ancestors, which had bound every Brethon ruler since the days of Tessaer al’Tyogg, and it was not for him to lightly give it up.

“False gods are false gods,” Ethred said, his words slurring, while the Janaean emissary, now seated across from Maibhygon, said something conciliatory, diplomatic — about the opening of Bryghala to missioners that was promised in the treaty.

“The treaty does not mention missioners,” Guernys said. It was the first time she had spoken to anyone save Maibhygon since she ascended to the table, and as her Narsil was better than the prince’s there was no mistaking the chill in the old woman’s voice. “Your faith has liberties in Bryghala; our queen herself has visited your temple. The treaty does not add to them; it merely welcomes certain of your inquisitors as advisers to our own effort against the cult of Yr’Aefae — this Black God.”

“The temple in question,” said Cresseda, leaning toward them from further down the table — “it sits in Cruimnh, does it not? A snug little city, I have heard, but perhaps a touch … provincial? A fortnight from Aelsendar, is not not? Surely our beloved princess will not be asked to travel so far to worship?”

Padrec saw Maibhygon and his adviser exchange a glance before the prince spoke: “My betrothed and any of her court who wishes will worship in Aelsendar. We have already made arrangements with the temple to see that your white priests are supplied, and of course if the princess wishes to bring …”

Alsbet spoke to Ethred, but really to everyone at the table listening: “My court will include both priests and sisters, cousin. You need have no fears on that score.”

Ethred started a harrumph but Cresseda’s voice cleaved through it: “That will be quite a change, then, given the laws of Bryghala, under which no priest save those of Bronh can enter the citadel of Aelsendar. Or do I not have your laws quite correct?”

The chill in Guernys’s voice dropped from wintry to glacial. “I am glad that your grace takes such an interest in our little kingdom. The truth is that this is custom and not law, which means that her majesty the Queen can order it suspended. As she shall when she welcomes her new daughter.”

“Ah, well, that is very fine!” the duchess returned, and her voice was all spring and warmth and music. “And no doubt our orders are very happy to have this change of custom included in clear language in the treaty?”

It was readily apparent that Archpriest Ethred, especially in his present condition, had no clear sense of what was in the treaty. In the midst of all of them Edmund the emperor spoke, his voice wavering a little. “Arellwen …”

But the chancellor, the treaty’s author, was now sitting somewhere down below, unavailable for clarifications.

“Should we send for the chancellor, your majesty?” said Jonthen Cathelstan in his most insinuating voice. “It would no doubt interest all of my fellow dukes hear more about the smaller details of this great arrangement.”

“There is no need,” said Prince Maibhygon, his gaze flicking to Alsbet and then back down the table toward the dukes. “I can tell you that in our marriage her highness shall reign as my equal, as is also the custom in our kingdom, and in joining herself with me she gains greater power over our laws than any mere — any treaty would afford.”

“And my betrothed and I have already discussed the question of widening the orders’ freedom,” the princess said, just a bit too sharply.

(“Have you really?” Padrec murmured to her, and her grip on his hand tightened.)

“Well, this is surely a feast and not some council meeting, my lords,” said Cresseda, “and I for one have no great desire to pore over every codicil of the treaty on Winter’s Eve. The princess’s words are reassuring, are they not, my lord Ethred? And no doubt it will be quite the change for the court in Aelsendar, Prince Maibhygon, to have a third faith represented in its halls.”

The prince seemed about to speak, and then stopped, while Cathelstan’s voice came in: “Dear Cresseda, what third do you mean?”

Are they the plotters? Padrec thought. Felcester and Argosa together, prodding tonight to test for weakness … it made a kind of sense. The desire to tell his sister about the plot became more powerful, laced with a feeling that was unfamiliar – a sense of something like protectiveness toward his father, his foolish grieving wine-ruined father, who was surrounded by wolves and didn’t know it.

“I’m just referring to the lure that the cult of this Black God, this Brethon fairy creature, reputedly holds for some the Bryghalan nobility. I do not mean to offend, of course, I merely repeat what I have heard.”

“One thing that is reaffirmed in our treaty, your grace,” said Guernys, “is that such worship is forbidden in our kingdom. I say reaffirmed because this is already the law under our queen. Your inquisitors will join an effort already in progress, to root out …”

“Yes, yes, but if some customs don’t quite have the force of law, don’t you think laws are somewhat less important than the custom of a country? And I have heard that this might be the case in your fair land – that for all the laws that forbid this black god’s cult, there has been until lately an understanding that leaves his worship unmolested.”

“This is not —” Guernys began, but Maibhygon made a gesture and she fell silent.

“What you have heard is correct, your grace,” the prince said, “but also incomplete. The cult that you speak of, that made its awful attempt upon my now-betrothed last year, was for a long time a matter for, what is the word, for rustics — a harmless thing, mostly bonfires and superstition that the throne and our sun god’s priests thought it best to tolerate. It is only since … since the late wars, that it has become something more, something dangerous. So the old laws have been given new force under the queen my mother, and the custom of toleration you describe has fallen away.”

“But not before, am I right, this cult fascinated a portion of your nobility?”

Padrec felt the sharp intake of breath from Alsbet, felt himself torn between suspicion of Cresseda and a desire to have her press the point to whatever end she had mind.

“As the cult waxed in strength,” Maibhygon said, “a very few nobles …”

“… a few nobles who are, perhaps, your friends and intimates?”

“… a few misguided nobles have participated in its services …”

“… in Aelsendar itself …?”

“… have participated in services which are now forbidden …”

“… but which took place for a time with your blessing …?”

“… no, your grace, that is not …”

“… and even with your royal personage in attendance …?”

“ENOUGH!” Edmund roared with unexpected ferocity, rising and smashing his plated flagon down upon the table. “You forget yourself, Cresseda. The Prince is more than our guest — he is my daughter's betrothed, and the heir to the throne of our ally, Bryghala. You will not . . . you will not badger him at the table of your emperor!”

There was a swift silence at the table, and a diminution in the cheerful noise within the hall. Beside Padrec Alsbet had half risen, releasing her brother’s hand, ready to move to her father’s side.

Padrec was still watching the duchess. Cresseda’s smile was a ripple on the stillness of her face. “I am sorry, Your Majesty. I am remiss. I hope that his highness will forgive my rudeness.”

Maibhygon nodded gravely. “Of course, your Grace.”

“Well, then,” Edmund said sharply, “let us have no more of it.” He sat down, gesturing for his flagon to be refilled. Alsbet moved to him, closing her fingers around his elbow and speaking softly in his ear.

The revelry rose anew, and the emperor's fool strolled past, singing about a lustful rooster. Another fool in black-and-white facepaint tumbled after him, shouting a children’s rhyme — almost familiar to Padrec, but with stranger words …

All around the wailing stones

The pretty maidens lie buried

Wash them in scarlet,

Dress them in silk,

And the first to rise shall be married!

Arellwen appeared now, at his emperor’s side. Edmund plucked at his sleeve. “Arell,” he murmured, “perhaps we should send for one of the harpers to sing for the table?"

The chancellor nodded. “An excellent idea, Majesty."

The emperor sank back between the carved falcons on his seat. His dukes watched him, Alsbet whispered to him, Padrec felt the brief feeling of filial loyalty slip away.

“And the first to rise shall be married!” shouted the fool.